Reds and Whites: A Work of Art Anchors Centennial Campus

Inspiration struck for Susan Woodson on an afternoon in the fall of 2019, an afternoon that seemed like any other as she strolled through Centennial Campus.

Glancing around at the scenery, Woodson couldn’t help but sense — despite the innovation she knew flowed through the classrooms, workshops and laboratories nearby — that the activity on Centennial’s sidewalks and plazas did not quite echo that same human energy.

That’s when the vision came.

“There are so many people at Centennial Campus doing amazing work, creative work, innovative work — but many people don’t see it,” said Woodson. “And I thought, ‘We need a visionary piece of outdoor art that will bring the larger community to this part of campus.’”

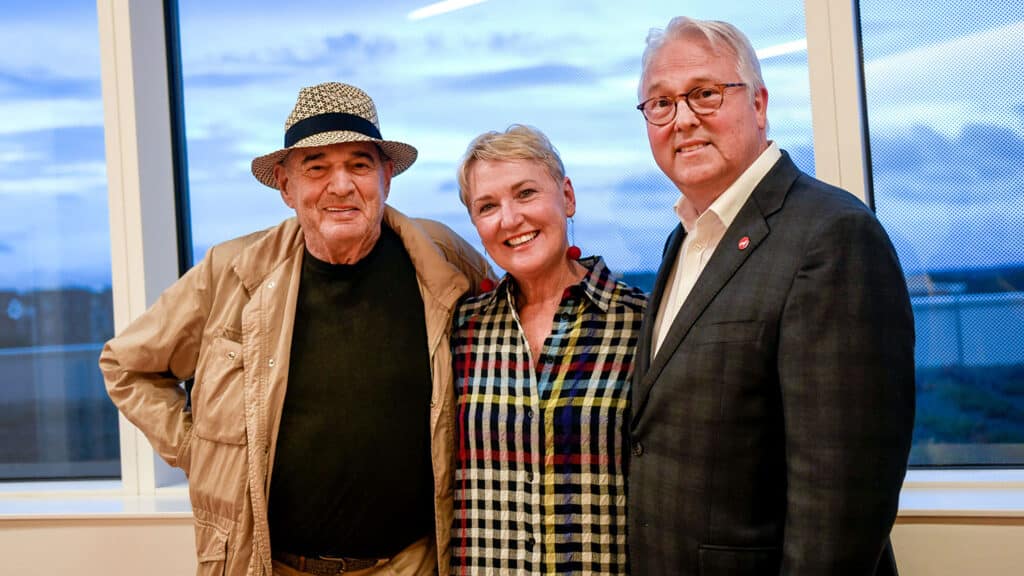

Woodson, an artist herself and an ardent champion of public art, relayed the idea to her husband, NC State Chancellor Randy Woodson. He liked it, and suggested she contact Larry Wheeler — recently retired after more than two decades as director of the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) — to discuss her vision and how it might be realized.

Wheeler, too, liked Woodson’s idea. Over coffee, the two decided to spearhead a committee that could raise private funds to bring a signature piece of public art to Centennial. In the weeks ahead, the Centennial Campus Public Art Committee formed around a nucleus of leaders including Woodson, Wheeler, Jude DesNoyer — a campus innovator committed to shaping Centennial into a hub of community activity — and Mark Hoversten, dean of the College of Design.

Committee members agreed their inaugural project should achieve two aims above all: It should feature a work of world-class art that could represent NC State’s leadership in the fields of design and engineering; and that artwork should be housed in a space — a plaza — that could bring people together and help anchor an enduring sense of place on Centennial Campus.

They chose for it a spot on the Oval, outside the east entrance of the James B. Hunt Jr. Library, itself an award-winning showcase of NC State’s creative prowess.

“It’s not an accident that we located this work on the Oval, right next to the Hunt Library,” said Hoversten. “We knew the plaza needed to be a fitting vessel for the artwork.”

An Artist To Realize a Vision

Half a continent away, New Mexico-based artist Larry Bell had spent an accomplished career investigating how the journey of light through sculpted glass could spark compelling visual interactions between his artwork and its surroundings.

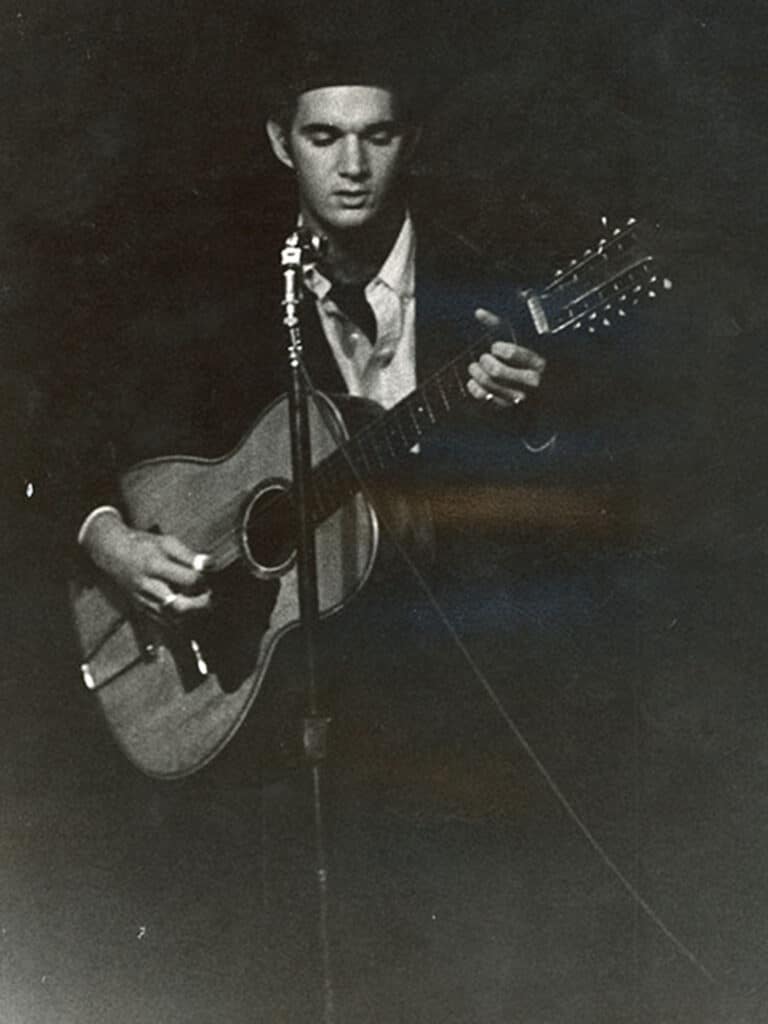

Internationally renowned by the art community, Bell’s involvement with the groundbreaking Light and Space art movement in southern California during the 1960s and his close ties to the era’s vibrant Hollywood music scene had — early in his career — landed him among the many faces filling the cover of the Beatles’ genre-busting 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. (Squint hard — he’s squeezed between two of the Fab Four.)

A younger Bell could not have foreseen the art — or the career — he would create. Born with hereditary nerve degeneration, which hampered his hearing, he struggled to keep pace with his classmates in grade school.

“I grew up not fully grasping the world as it was,” said Bell. “Because of that, I did terribly in high school. But I liked to draw cartoons. In fact, the only time I ever got a good grade in school was if I turned in my homework assignment in the form of a comic book.”

Bell’s realization that he enjoyed — and excelled at — the creation of art inspired him to apply to the Chouinard Art Institute in his hometown of Los Angeles. He was accepted, and at Chouinard, during the late 1950s, Bell blossomed as an artist through his experiments with painting in the abstract expressionist form.

Bell, however, felt he had not quite found his place.

“Because of my hearing problems, I think I had a similar problem in art school that I had in high school,” he said. “I enjoyed some of my instructors, but in general, I was sort of depressed with myself and the situation.”

Spurred on by his mentor, installation artist Robert Irwin, Bell left Chouinard in 1959 to find his own artistic calling, forming a fledgling studio in a garage attached to his small L.A. apartment. To pay the bills, he took work at a shop that framed art for paying customers and sold picture frames and shadow boxes — frames with added depth, often used to display items of special importance.

One day, after cutting a glass piece to place in the front of a shadow box, Bell accidentally cracked the glass as he moved to fasten it to the maple frame. Disappointed, he considered starting over. He chose instead to finish the box with the piece he’d fractured. At that moment, “the most extraordinary thing happened.” In what he’d thought was a mistake, Bell now saw a three-part composition: the crack in the glass, its shadow, showing behind — and its reflection, flashing forward.

“All the parts just happened,” said Bell. “But I was responsible for everything that happened — the selection of the box, the color of the paper backing, cutting the glass, breaking the glass — and it was my decision to proceed with it and not cut another piece. Those facts gave me confidence to pursue something that had to do with this box of space and glass.”

Bell grew transfixed by glass and its trinary tendency to absorb, transmit and reflect light, all at the same time. The revelation put him on an artistic path toward shaping glass at scales meant for human immersion — which placed Bell on the radar of those now looking to bring an inspired work of art to Centennial.

A Vision Comes to Life

By early 2020, members of the Centennial Campus Public Art Committee were seeking the artist who could realize their vision. As names were tossed about, Wheeler suggested the committee contact Lauren Ryan, an NC State alumna who had worked with Wheeler at the NCMA, and now worked as a partner at Anthony Meier Fine Arts, a gallery in San Francisco.

The committee asked Ryan if she could recommend an artist whose work reflected the pioneering spirit of the Wolfpack. She suggested one of their gallery artists, Bell, whose large-scale glass pieces required a mix of artistry and engineering to construct. Woodson, Wheeler, Hoversten and others on the committee agreed to travel to Austin, Texas, to meet with Bell, who would be visiting the city for the dedication of one of his pieces in a private gallery.

“Honestly, I had not thought about glass being out there at all,” said Woodson. “But then I saw Larry’s work, and I thought, ‘This really represents all the innovation going on at Centennial, and he’s a world-renowned artist’ — it just fit together.”

Bell, yearning to “do something big,” a work that people could engage with in an open setting, visited Raleigh in February of 2020 to meet the full committee and view the space they’d selected. Over dinner and drinks with Woodson and her husband, the artist and the chancellor bonded over their shared love of music and guitars.

“At one point, Randy asked Larry to play the guitar — and Larry said, ‘Well, I don’t play anymore, I just collect,’” said Woodson, smiling. “But they hit it off, and Larry loved the space we had chosen.”

A few weeks later — with Bell’s commitment secured — Hoversten, serving as executive architect, and Tom Skolnicki, a university landscape architect brought on as architect of record, visited Bell’s studio in Taos, New Mexico, to finalize plans for the plaza and the art.

In Taos, Hoversten and Skolnicki watched as Bell and his team of artists and engineers lowered large pieces of reinforced glass into a vacuum chamber — 20 feet long by eight feet high — then vaporized metal alloys to settle upon the glass, imparting patterns that changed how the pieces responded to ambient light. Conferring with the artist by day, the architects returned to their hotel at night to reconfigure and revise.

“By the end of our week in Taos, we had pretty much roughed out the concept we have now,” said Hoversten.

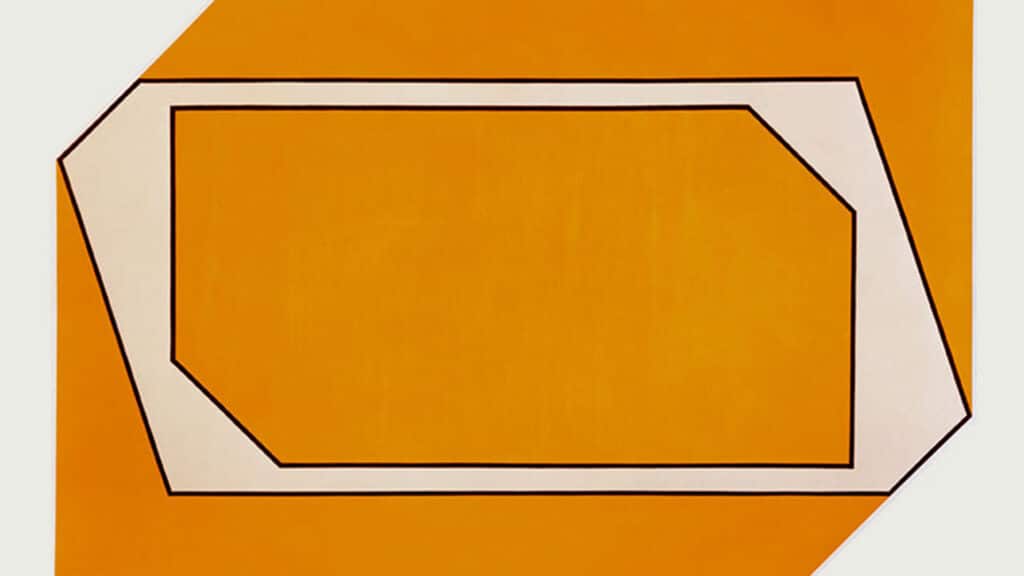

That concept centers on a series of human-scale glass cubes and components of cubes — shapes that proliferate in Bell’s artwork — clustered in four sections in a central plaza and flanked, to the east and west, by bosques of trees. The work, called Reds and Whites after the Wolfpack’s favorite colorway, includes a mixture of red pieces, white pieces and others of an indistinct hue.

“It’s a frosty piece of glass that has no color to it,” explained Bell. “But if you look through it at another piece that’s red, a diffused kind of pink comes through. And when the sun moves over the right-angle pieces, it casts their shadows on their neighbors.”

The COVID-19 pandemic delayed completion of Reds and Whites, but it didn’t derail it. The work was unveiled last week, and its plaza was dedicated, becoming the Susan Woodson Plaza, in honor of the woman whose vision and hard work led to its creation. While Larry Bell so kindly furnished the artistry, the engineering was a product of partners across NC State, from the University Libraries and Facilities to the College of Design and College of Engineering. Additional support, including private donations, came from beyond our campus.

Learn more about how private donations brought this world-class work of public art to Centennial Campus.

Reds and Whites was funded entirely by private donations from nearly 40 families, corporations and individual donors. Dr. Jim and Ann Goodnight, generous supporters of NC State and North Carolina’s public arts, provided the naming gift for this project and chose to honor Susan Woodson by permanently naming the new gathering space the Susan Woodson Plaza.

“We are so pleased that the Goodnights wanted to name this space in honor of Susan for her incredible leadership on this important project,” said Brian Sischo, vice chancellor for University Advancement. “The Susan Woodson Plaza is a testament to her legacy of leadership and steadfast support of all things Arts at NC State.”