Design Thinking in Law

Written by Stuart Hall

On the surface, the idea of combining design thinking with the practice of law appears a bit unconventional — something akin to mixing peanut butter with a banana to make a sandwich. The result, though, can be appetizing.

When Tsai Lu Liu, an N.C. State University professor and Department Head of Graphic Design and Industrial Design, was approached by Kevin P. Lee, a Campbell University law professor, about collaborating on a course, “Design Thinking for Law Students,” Liu was more skeptical than curious.

“First of all, I was very surprised,” Liu said. “I was not as surprised when the engineering school or the business school approached us about integrating design thinking, because they have similar interests as us as designers, which is to make a product or design or technology more appealing to customers or consumers.

“What is differentiating them is how they are creating a better client experience. So design thinking is helping good lawyers become better lawyers.”

“I wondered why law students and lawyers would be interested, but I quickly realized they are very interested in not necessarily being more creative, but more adaptable to new technology and also very interested in the user-centeredness of their profession.”

The course, co-taught by Liu and Lee, focused on human-centered design through the process of empathizing, visualizing, prototyping and iterating. While other universities such as Duke and Stanford have offered similar classes, those classes have been taught from a law perspective. Liu brought his industrial design background to this equation.

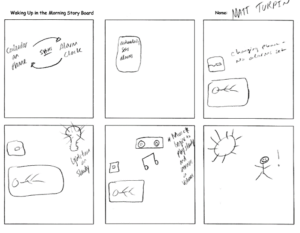

On one of the class’s first days, Liu asked the second- and third-year law students to take a piece of paper and draw an object. They were perplexed but ultimately proved to be more creative than Liu anticipated.

“They were like ‘We didn’t sign up for drawing,’” he said laughing. “The purpose was not to create something beautiful but to not be afraid to use their hands and their pencils to create ideas. And some of their drawings were comparable to some design students’ drawings in terms of trying to tell stories and to iterate their ideas.”

“They were like ‘We didn’t sign up for drawing,’” he said laughing. “The purpose was not to create something beautiful but to not be afraid to use their hands and their pencils to create ideas. And some of their drawings were comparable to some design students’ drawings in terms of trying to tell stories and to iterate their ideas.”

The purpose of this collaborative effort was to help would-be lawyers create a better user experience. Liu used the medical profession as a parallel example. The basic function of a physician is to heal patients, but to be more successful in this era of creating relationships, the physician also needs to develop a better patient experience. Liu notes that many hospitals around the country are measured on that basis.

“There are many attorneys who are successful,” Liu said, “but what is differentiating them is how they are creating a better client experience. So design thinking is helping good lawyers become better lawyers.”

For the course’s final project, students went into the field to learn how people use a legal service and interact with lawyers, identify problems and then create opportunities to improve the experience. One student’s final project, for example, focused on divorce attorneys and how that niche industry could improve the oftentimes emotional process. The results ranged from firms making their office settings less intimidating and more comfortable to working with other partners to offer services such as financial planning and counseling.

The reason for the industrial design thinking approach, Liu said, stems from around the Industrial Revolution. Prior to the revolution, artisans and designers could produce products tailored to a smaller segment of consumers. The revolution, though, changed that.

The reason for the industrial design thinking approach, Liu said, stems from around the Industrial Revolution. Prior to the revolution, artisans and designers could produce products tailored to a smaller segment of consumers. The revolution, though, changed that.

“Industries started making thousands of products, so if a design pleased only a small group of people, the product was not going to be successful and the company was going to lose money,” Liu said. “Industrial designers understood that they needed to come up with a design or product that would appeal to a larger audience. Over time they understood this importance and borrowed many tools to reach a better understanding of the people they were designing for. Businesses and marketers also do that, but designers do it differently, they put more attention into a person’s interaction with the product or service.”

Marketers, Liu suggests, look at consumers like a forest as a whole, while designers look at consumers a single tree at a time “to understand their experience, their aspirations and their problems,” he said. “Based on this we can create solutions that will improve current situations. They look at situations not just as physical experiences, but emotionally and culturally. Designers have to be work with anthropologists, sociologists and psychologists.”

- Categories: