Cementing a Partnership

Written by Meghan Palmer. Published in Designlife Magazine in November 2017.

How something is made can impact how it’s designed—a principle Associate Professor of Architecture Dana Gulling impresses upon students in her studios, where young architects learn to bridge technology and design as they innovate ideas for new structures.

For Greg Lucier, Research Assistant Professor in Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering, understanding the broader impact of production details in building materials is key to the research he and his students perform as they test structures at full scale in the Constructed Facilities Lab (CFL).

These two disciplines—architecture and civil engineering—while tangential, often did not overlap in the courses at NC State until recently, when Gulling and Lucier teamed up to create an interdisciplinary endeavor that blended the studio learning environment with structural engineering.

Creations in Concrete, a new ARC 503/CE 675 studio that started in Spring of 2017, brought together architecture and civil engineering students to study precast concrete. It’s a type of concrete that, unlike standard concrete, is poured into a mold and cast before being transported to a building’s construction site. Its use in the industry is becoming more widely accepted because it allows for more efficient construction, better quality control, and greater design flexibility than traditional concrete, which must be poured and erected on-site.

The studio was sponsored by the Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI), which provides grants to educational institutions like NC State in order to better familiarize students with precast concrete as a structural and architectural material. Peter Finsen, a member of PCI Foundation’s Board of Trustees, kicked off the studio with an introductory lecture. “Civil engineering typically teaches a prestressed concrete course, and [those students] are more familiar with it than architecture students,” said Finson. “But it’s a great experience that provides foundation in the industry.”

“I think precast, probably more than any other building system, requires a close link between design, fabrication, and construction,” Lucier explained. “Those disciplines have to be viewed holistically. With other types of construction, you can do the design and not worry about who’s going to build it, or vice-versa. But with precast, some of the things that make it very unique can also make it unforgiving.”

That link between design and practice made precast an optimal subject material for a studio that sought to fuse the worlds of civil engineering and architecture, worlds traditionally, but perhaps not deliberately, kept separate from one another despite their natural synergy. “Before integrated practices came up, you would get to a certain point in design development and then send it off to the structural engineer,” Gulling said. But recent innovations in materials like precast have taken a process that was previously linear and created an opportunity for collaboration.

During the studio, nine architecture students and four civil engineering students collaborated on three projects that investigated precedent, component design and fabrication, and full building design concepts. Activities within the studio ran the gamut from reviewing case studies, to touring manufacturing facilities, to attending the PCI trade conference in Cleveland, to even working hands-on in the Materials Lab with US Formliner, a company that graciously provided rubber for molds which the students could cast on their own.

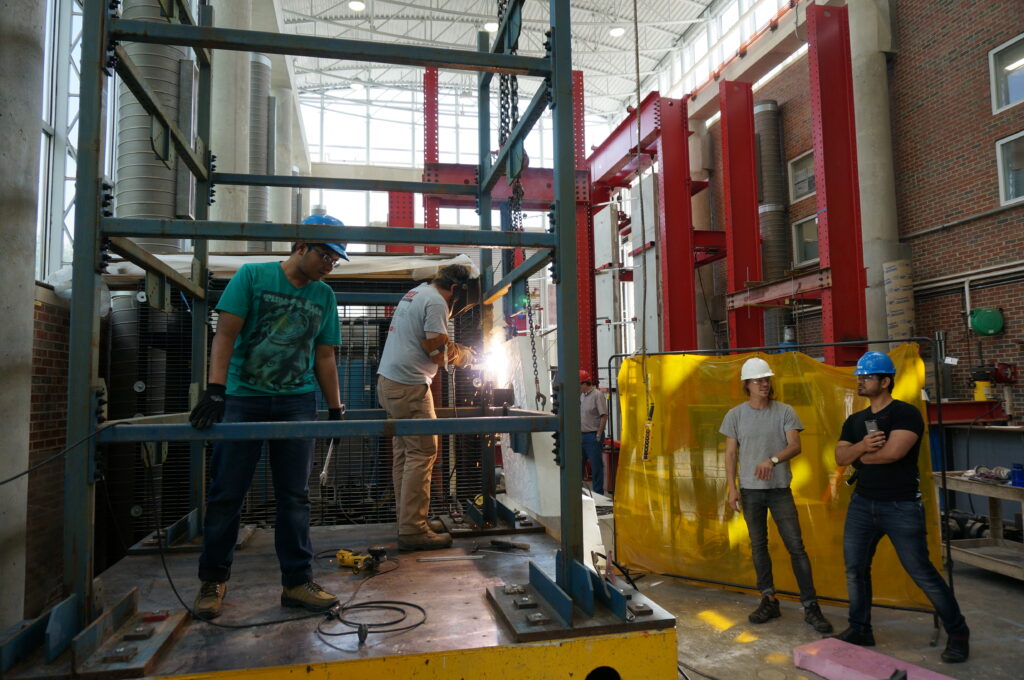

Perhaps the most impactful part of the studio, however, came from the time the students spent in the CFL, constructing and testing full-sized precast concrete panels as part of their final project: conceptual designs for a cidery in Upstate New York. Such a building appealed to Gulling and Lucier because the combination of small spaces nestled within large spaces offered an ideal challenge. And it helped that the site was accessible by the students, some of whom made the journey over Spring Break to assess it after attending the PCI Conference.

For Lucier and engineering graduate students like Meghan Strahler, the Creations in Concrete class was their first exposure to a studio-based environment outside of a classroom, where the emphasis was on creating a solution to an open-ended problem instead of listening to lectures and completing textbook-based problems.

“Working with the architecture students was a very eye-opening experience. Learning to cooperate and communicate effectively was critical,” said Strahler. “Visiting precast concrete plants and participating in the casting of wall panels afforded me a feel for what was practical to achieve in construction beyond what design calculations may indicate.”

Eye-opening: it’s a phrase students and faculty alike used often during the course of the studio, working with a subject that Lucier believes one must witness firsthand to truly understand. “It’s one thing to say, ‘Weld a steel beam up there,’” he explained. “But if I say, ‘I’m going to pour this concrete into this mold and it’s going to look nice and it’s going to have all the attachments we need to get it on the building,’ that’s a harder sell until you see it.”

For Austin Corriher, who was a senior in architecture at the time he took the class, these real-world interactions with an interdisciplinary focus were both challenging and rewarding. “I’ve never actually gotten the chance to meaningfully interact with another non-design major in a studio before,” he said. “The immediate feedback of someone grounded in the real world came back to help after every design decision, even if a lot of them told us, ‘No, this cantilever can’t be 60-feet long.’”

And giving the students the opportunity to work together on their designs in the CFL was a large part of the studio’s impetus. “We really wanted to use this facility as an opportunity,” said Gulling. “Especially in the school of architecture—we have such a great legacy and an interest in having the students make things.”

Students and faculty alike came away from the studio with a greater respect for both design and engineering, and they were challenged in their own practices to optimize and innovate their approach to problem-solving. And Finson, who represented the PCI Foundation when he visited NC State for the final critiques, praised the projects and the participants. “Dana and Greg did a great job working together with the students,” he reflected. “That kind of collaboration is what makes the studio a success.”

- Categories: