Universal Design Welcomes Everyone

Karen Swain: Photo credit

A visit to the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (NCMNS) wouldn’t be complete without admiring the “Terror of the South” on the third floor. This exhibit, housed in a three-story, glass-domed rotunda, is home to the fossilized skeleton of an Acrocanthosaurus, a 13-foot-tall predatory dinosaur that looms above visitors. It lunges, jaws spread to show 68 deadly teeth, at a life-sized model of its prey, a Pleurocoelus lashing its tail in front of a painted backdrop that evokes the Early Cretaceous Period. Suspended from the domed ceiling on wires are winged Anhanguera, or pterosaurs.

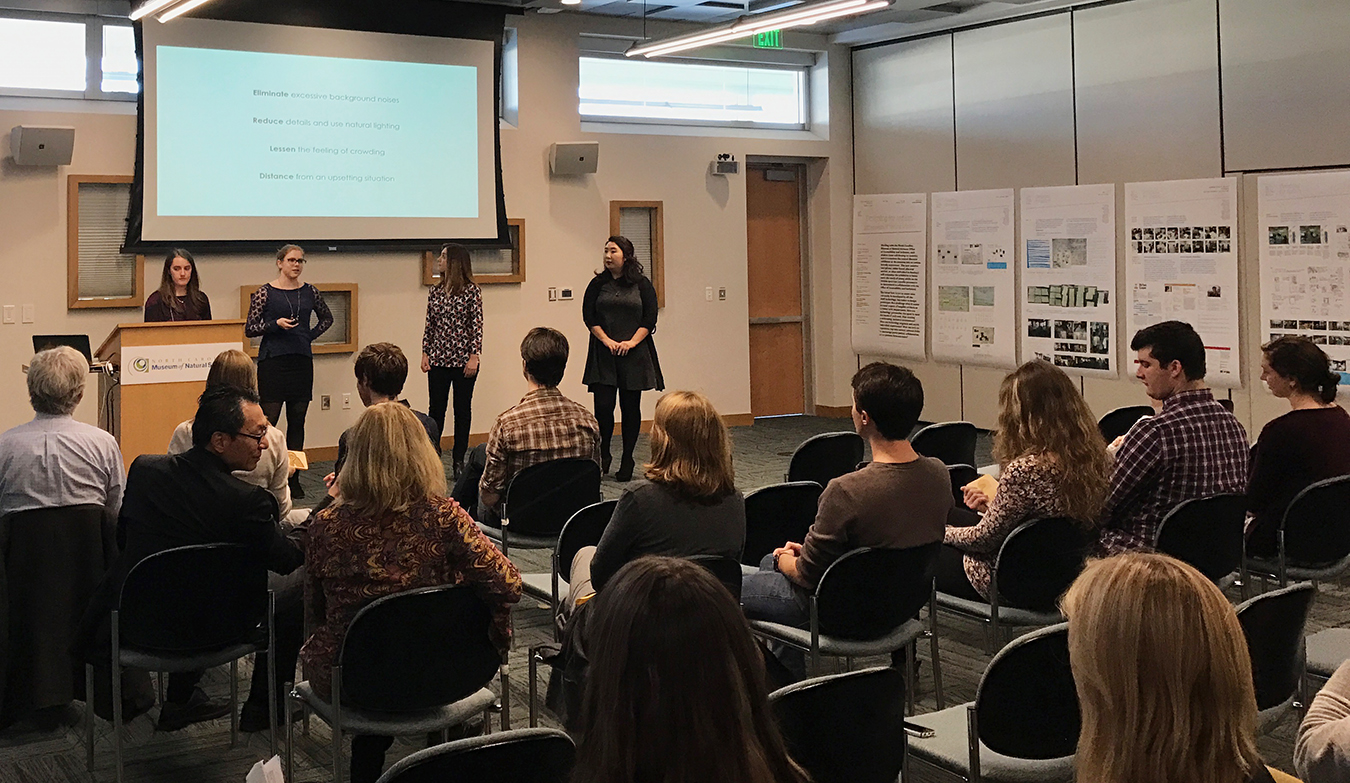

Most museum patrons might be a little overwhelmed by the sight, not to mention the presence of other visitors and their children zig-zagging through the room as their excited shouts echo in the bright space. The noise, the crowds, the variable temperature in the room (difficult to control due to its size), and the lack of structure at the exhibit can be downright unwelcoming to individuals with autism—and the museum wanted to explore design solutions to change that. In parallel studios taught by associate professors of graphic design Helen Armstrong and Scott Townsend, students of the College of Design came up with ways to make a visit to the museum—complete with a jaunt to the Acro exhibit—more inviting.

“These kinds of central exhibitions of very large dinosaur specimens are key attractors for many natural science museums, but these spaces are very challenging for individuals with autism. The museum identified young adults with autism as users they wanted to rethink the experience of this space for—this particular population sometimes didn’t even want to enter the space,” says Armstrong. Although redesigning a keystone exhibit like the Acro display is an expensive proposition, “interventions” can be integrated into such spaces to include the needs of individuals with autism and any number of other conditions or disabilities.

Armstrong’s senior special topics studio and Townsend’s sophomore GD 201 studio collaborated for thoughtful solutions by splitting tasks: Townsend tasked his students with researching the history of autism and assistive design, assistive devices, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. They also created a promotional campaign to welcome visitors with disabilities to the museum. Armstrong’s students took on designing for the Acro exhibit.

The needs of autistic individuals vary widely across a spectrum; in order to really cater to this group, the students developed individual personas they could focus on in their ideation process. “Each and every individual is as varied as you and me; we all have different learning aptitudes and interests, and you could not assume that a given design solution is going to be one-size-fits-all,” says Roy Campbell, NCMNS Chief of Exhibitions & Digital Media, and the main liaison between the museum and the college. “You have to go deeper than that and personalize—that’s where the class outcome was terrific. These personas had a form of autism, but each irrespective of that had their own interests and other attendant challenges. That really bore fruit; that’s what helped catalyze these really interesting approaches that the various students came up with.”

The needs of autistic individuals vary widely across a spectrum; in order to really cater to this group, the students developed individual personas they could focus on in their ideation process. “Each and every individual is as varied as you and me; we all have different learning aptitudes and interests, and you could not assume that a given design solution is going to be one-size-fits-all,” says Roy Campbell, NCMNS Chief of Exhibitions & Digital Media, and the main liaison between the museum and the college. “You have to go deeper than that and personalize—that’s where the class outcome was terrific. These personas had a form of autism, but each irrespective of that had their own interests and other attendant challenges. That really bore fruit; that’s what helped catalyze these really interesting approaches that the various students came up with.”

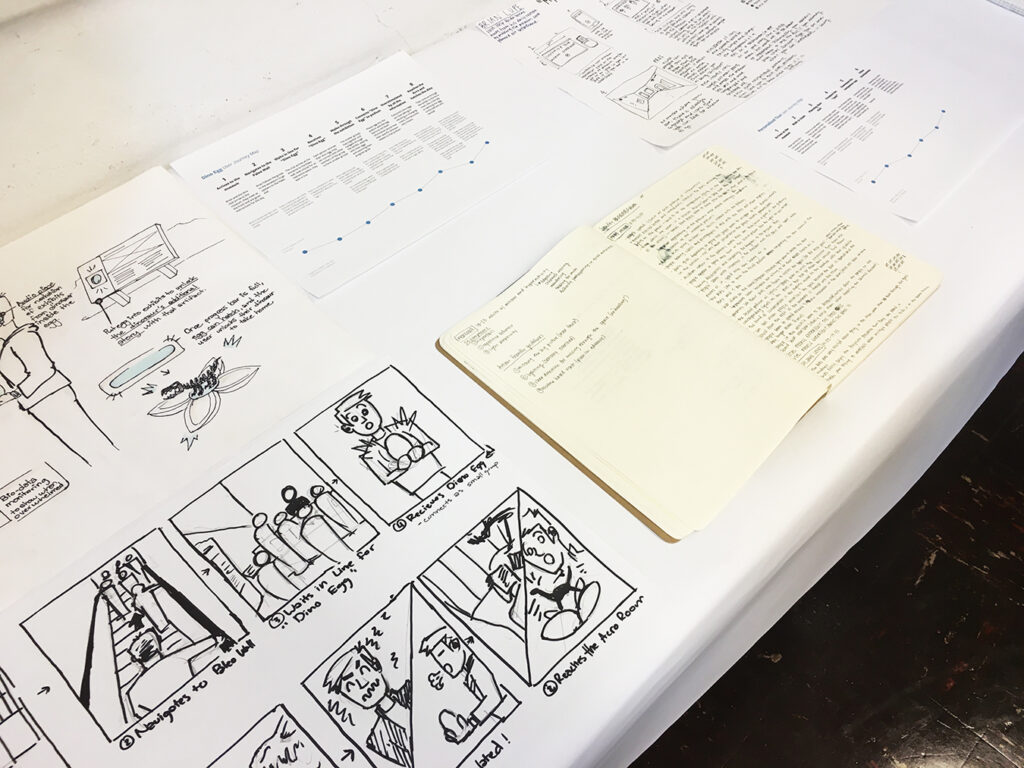

Campbell, who in his day was asked to develop solutions for the visually impaired at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and two other NCMNS staff members visited the studio to provide feedback throughout the process. The Autism Society of North Carolina reviewed students’ personas for accuracy before they continued on to making user journey maps that allowed them to envision a typical visit to the museum by their persona and the challenges that persona might encounter. Then, students took their sketches and revised journey maps and went “bodystorming” to the museum. With props to represent their interventions, they put themselves in the shoes of their personas and followed their trails through the museum.

One project involved the placement of “pause pods” throughout the museum. Armstrong describes these as “spaces you can go into to have a quiet moment of reflection, separated from the rest of the population. They’re for anyone to use who starts to feel overwhelmed with the chaos and needs a moment of quiet.” They would still offer a view of the exhibits, but users could also focus on the interiors of the pods, which are lined with interesting textures. “If you like to explore textures as a calming exercise, you can do that,” Armstrong explains.

One project involved the placement of “pause pods” throughout the museum. Armstrong describes these as “spaces you can go into to have a quiet moment of reflection, separated from the rest of the population. They’re for anyone to use who starts to feel overwhelmed with the chaos and needs a moment of quiet.” They would still offer a view of the exhibits, but users could also focus on the interiors of the pods, which are lined with interesting textures. “If you like to explore textures as a calming exercise, you can do that,” Armstrong explains.

Other solutions included giving visitors a device to wear like a necklace that they could lift to their ear for guidance through the museum. In a soothing voice, a recording would offer facts or “secrets” about the exhibit, or ambient music that might add to a visitor’s experience. Another student group researched bone conduction technology, called Soundimaginings, that has been used as a way to direct sound—in this case by transmitting it through a railing that participants place their elbows on while cupping their hands over their ears. This could be applied to the fourth-floor overlook of the Acro exhibit, offering a narrative at a distance that would still connect visitors to the scene below. Not only would users have control of the experience by raising and lowering their hands at any time, but the action of putting one’s hands over one’s ears wouldn’t appear out of the ordinary. “This is something that is very common if you feel overwhelmed by stimulation,” Armstrong says. “It’s taking a gesture that’s very common to the users that we’re trying to serve here and normalizing it, so a lot of people are doing that now, and it doesn’t seem odd. It’s a part of the museum experience.”

Although the museum has visual aids and maps on its website, students also offered suggestions as to how visitors could better plan their journeys through the museum to create added structure for the individuals who most need it. Preparing for the trip, and finding calm spaces where visitors can catch their breath between busy installations, can make a huge difference in the success of a visit.

“I’ve gotten a lot of great feedback from students about this project,” says Armstrong. “They felt they were positively impacting the world through this project, and they found that very meaningful. Autism has become a very prevalent condition in our society, and most of the students had a lot of very personal connections to autism.” One student based her persona off of a childhood friend with autism, and another considered his autistic brother’s needs when researching.

Ultimately, the students’ design solutions had broad applicability. They not only met the needs of their specific personas but had wider implications. And this is what inclusive design is all about. “The best solutions end up being universal design solutions,” says Campbell. “The benefits really are society-wide. They touch upon everyone, if not now, then sooner or later, so it’s to our benefit to support these solutions, and it’s very much to our benefit that the up-and-coming generations of designers are imbued with a better understanding about the nature of the subject.”

The NCMNS is working with Gensler Architects to improve the visitor experience of the main museum building, which was erected 17 years ago. As they move forward, the concepts explored by College of Design students will inform their process. Because of the collaborative nature of the studio, the students are free to include their designs in their portfolios and to further develop them. Armstrong fully expects that these ideas will remain with her students as they graduate and go out into the world. “This [project] was about building empathy but also about students figuring out who they want to be in their design practice, who they are serving, and how they want their work to impact society,” she says.

Julie Steinbacher [MFA ’16] is a transplant from Parkton, Maryland. She writes science fiction, and her story “Chimeras” was a Notable Story in this year’s Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy. She lives and works in Raleigh, NC, as a freelance writer and editor. To read her fiction, visit http://julie-steinbacher.com.