Nothing is Perfect: Meditation, Virtual Reality and Juvenile Justice

They Just Want to be Kids

Megan Mercurio teaches English to students ages 12 to 18 who are detained at the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) Court School, also known as Woodside Learning Center. An overwhelming majority of students arrive at Woodside from poverty. Many of them come from group homes, from which they often run away. The result of running away is more missed school as well as a probation violation and often, an arrest for a non-criminal offense. Once arrested, it’s back to Juvenile Hall.

The cycle of recidivism – the return to detention after release – can seem impossible to escape when there is no safe space to run away to.

Yet once kids return to Woodside it is not uncommon to see them with beanie babies perched on their shoulders during class, or vying for smelly stickers to place on their folders. The students’ appreciation of these things is a compelling reminder that they are still children in need of comfort, protection and hope.

“A lot of them didn’t get to have a childhood,” says Mercurio. “They were forced to deal with such adult strains and responsibilities from early ages. Many of the students do not have stable home environments or a support system. They have learned to hide behind the mask of being unreachable and uncaring, but in reality, they just want to be kids.”

Currently, one of the largest challenges Woodside kids face is a mandatory 14 day quarantine period upon arrival due to COVID-19. Although they aren’t completely isolated from the other kids in quarantine, they don’t have access to cathartic amenities like the gym, the garden or the classroom.

Mercurio heard about the College of Design from her brother-in-law who attended the annual SIGGRAPH conference, where he was introduced to the “I Am A Man” VR experience by Art + Design Department Head, Derek Ham.

“After seeing ‘I Am A Man’ I knew that my students would love to have an experience like that,” states Mercurio. “I wrote to Derek, and said, ‘Hi, I’m this random teacher from San Francisco. Do you want to chat?’”

A World Without Walls

Upon hearing about the program at Woodside, Ham saw an opportunity for his ADN 560 graduate students. In the studio, his students were tasked with developing a conceptual VR game that is tailored to the specific needs and issues faced by incarcerated youth.

Mercurio’s students were already getting acclimated to VR as a complement to academic subjects in her classroom. Using the headsets, they were able to explore astronomy, oceanography, biology and various world wonders and landmarks. Mercurio wanted to explore VR applications that could also be healing based on student interest and engagement with VR headsets for study.

“If anything, putting these kids into a better mood to me is a win,” reflects Mercurio. “Experiencing something like the solar system through a book is very different than experiencing it from space. Using VR, they can explore topics that are usually less accessible to them. A lot of my students haven’t even left the city. With this tool, they can have a completely new, common experience.”

Each game to be developed in Ham’s studio needed to take into consideration a wide variety of factors and questions, such as: What is the best way to work with those who have undergone trauma and traumatic situations? Is it best to create an educational, remedial or entertaining program? How does this program fit into the current social divisions during incarceration?

Imperfect, Impermanent, and Incomplete

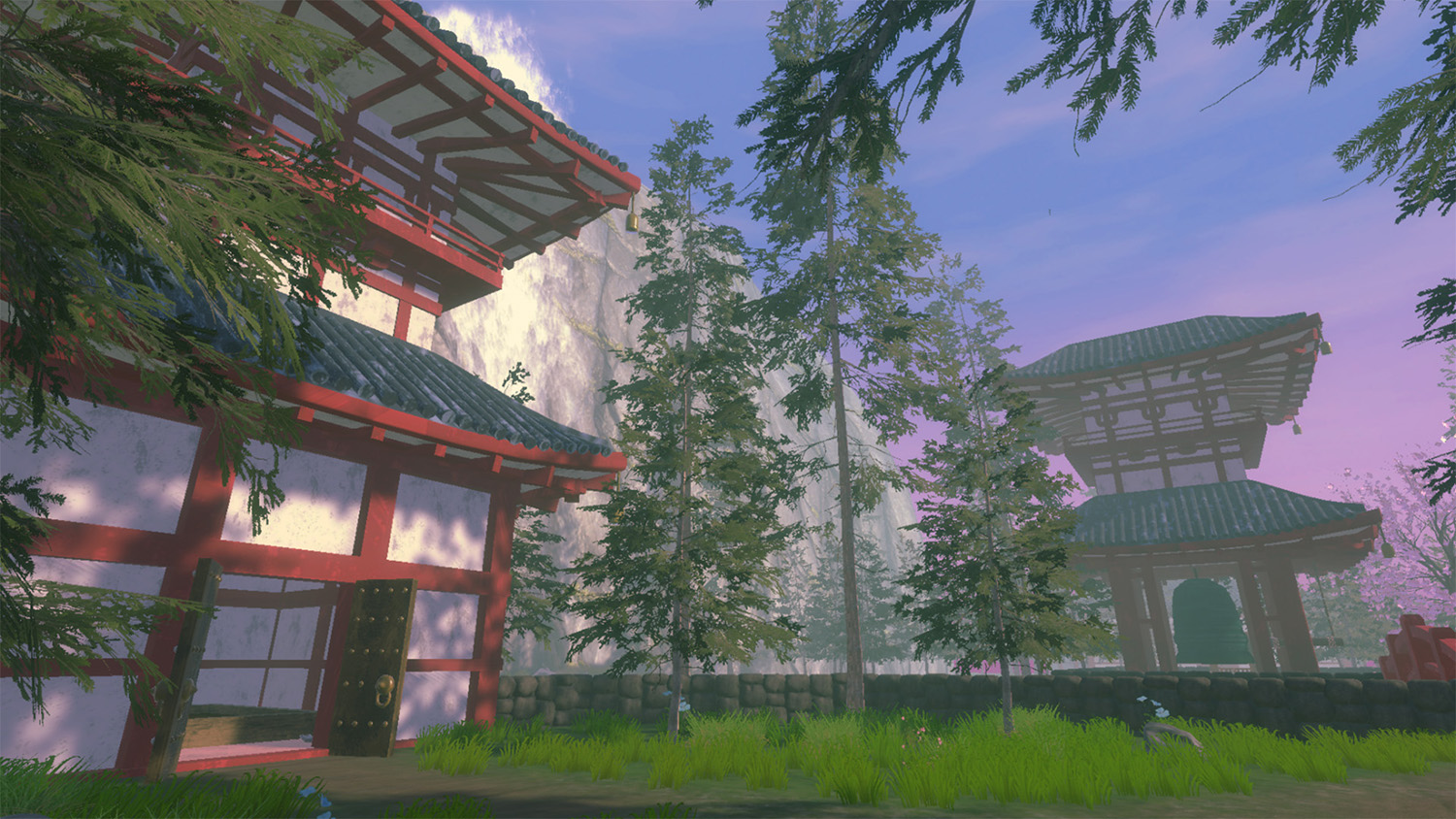

Partners in life, as well as game design Izzy Daniels and Mitchell Connor, are working together as part of the ADN 560 studio. Their game, titled “Wabi-sabi,” focuses on meditation and environments through the Buddhist philosophy of the same name which emphasizes transience and imperfection.

Daniels and Connor chose the theme after discussing the students’ needs with Mercurio – discovering that many of them had a significant interest in Asian cultures. They concluded that, for kids who are required to do so many things, there could be a benefit from an environment that allowed for active non-participation.

“We read a lot about the importance of play in a developing brain, as well as research on institutional racism and racism within the education system,” says Daniels. “Our main goal was figuring out how to make a space that the students could benefit from the most emotionally and mentally within small bursts of gameplay.”

In Wabi-sabi, students have the ability to create colorful sand mandalas, relax near a koi pond and meditate in a rock garden. The game is not designed for the user to accomplish a goal. The user can simply be.

While not completed during the course of the studio, Izzy and Mitchell are both continuing to develop Wabi-sabi independent of their coursework. They both credit Ham, Mercurio and their fellow studio mates with encouraging their progress.

“We also cannot overstate the importance of having a good cohort,” says Daniels. “Our peers are amazing and incredibly supportive with every project – we are very lucky to have such a great team!”

Mercurio is also looking forward to seeing the project develop further, and hopes that programs like Wabi-sabi can make it into the hands of her students at Woodside. After facing a school-wide hiatus from the program over the summer, she was notified that she can restart the program with VR in even more housing units than before with the assistance of her student, Joy.

“I feel like this is just the beginning,” says Mercurio. “Even though VR content for students is still fairly limited, there’s just so much more that can be done. The whole process has really changed my outlook. This can help make a radical change, and I’m so excited to see what’s next in this experience.”

This post was originally published in College of Design Blog.