Architecture: The First Seventy-Five Years

This article was written by Patrick Rand, FAIA, DPACSA, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Architecture, Roger Clark, FAIA, ASCA Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Architecture, and David Hill, FAIA, head of the School of Architecture, to capture the history of the program as part of the reflections on the College of Design’s 75th anniversary in 2023.

__________________________________________________________________________

“In 1948, in this unlikely setting on Tobacco Road, a new School of Design was founded and a new educational idea was given birth. At the core of the school in these early years was an uncompromising belief that comprehensive design would produce a healthy environment, and improved society, and a better life for all. Experimental in nature, the School was open to new ideas and challenges. It identified with the progressive aspirations of the new south, but its perspective was global. Unlike many of its peer institutions emerging from traditional academic positions, the school’s zeal for the new was balanced by an uncommon concern for the broad development of the individual student who was expected to assume a formative role as a creative leader and committed citizen.”

– Robert Burns

Reflections and Actions: An Inspiration for the Future, 1996

Architecture was one of the two original departments in the School of Design when it was founded in 1948.

In 1946 Dean Harold Lampe of the School of Engineering and Dean Leonard Baver of the School of Agriculture proposed to Chancellor John Harrelson to form a new School, bringing together the Department of Architectural Engineering and the Department of Landscape Architecture. The chancellor formed a search committee to identify and interview candidates in the fall of 1947. Henry Kamphoefner, then a professor of architecture at the University of Oklahoma, was offered the position as founding dean of the School of Design.

Clarity of Vision

Henry Kamphoefner accepted the offer with several unusual stipulations. He, to a great extent, cleaned house of the faculty and existing department head. The stipulations were:

- The existing head be replaced by “a man of national reputation.” Within one year Matthew Nowicki was named acting head of architecture.

- An existing tenured professor’s resignation was obtained.

- Five existing non-tenured professors were terminated.

- Four existing faculty were retained.

- Six new faculty were hired, with a 60% increase in salary compared to the six that were replaced.

- Four of these six were hand-picked by Henry Kamphoefner from the University of Oklahoma: James Fitzgibbons, Duncan Stuart, Edward Waugh and George Matsumoto.

- One faculty position was kept vacant, to fund the new Distinguished Visitors Program.

The new academic unit was named the School of Design and included architecture and landscape architecture. The Head of Landscape Architecture was Gil Thurlow, who had served on the search committee for the new dean. None of the school faculty had tenure; all had one-year contracts that were revisited annually by the dean.

Dean Kamphoefner displayed a clear vision to establish in only a few years an institution of national and international prominence. He used all means available to him, including the curriculum, faculty and student selections and negotiations for university resources to achieve this goal. Equally quickly, the School of Design became the darling of the university, attracting national attention vastly out of proportion with its size or age.

Key elements making up the foundation for the architecture program were:

- Singleness of purpose: The authoritative dean intentionally brought in faculty with diverse talents, interests, and worldviews. They squabbled, but the design pedagogy held them together.

- Faculty were hand-picked by the dean, even after the initial founding. They were teachers first and practitioners second. Faculty were hired for their excellence, not to teach a particular topic. Later they would figure out what they would teach. Faculty interests drove the curriculum, not the other way around.

- Faculty were required to practice in their discipline. Practice was their research. This is where the pedagogy was put to the test. Proof of concept was revealed and disseminated publicly through built works, articles and awards.

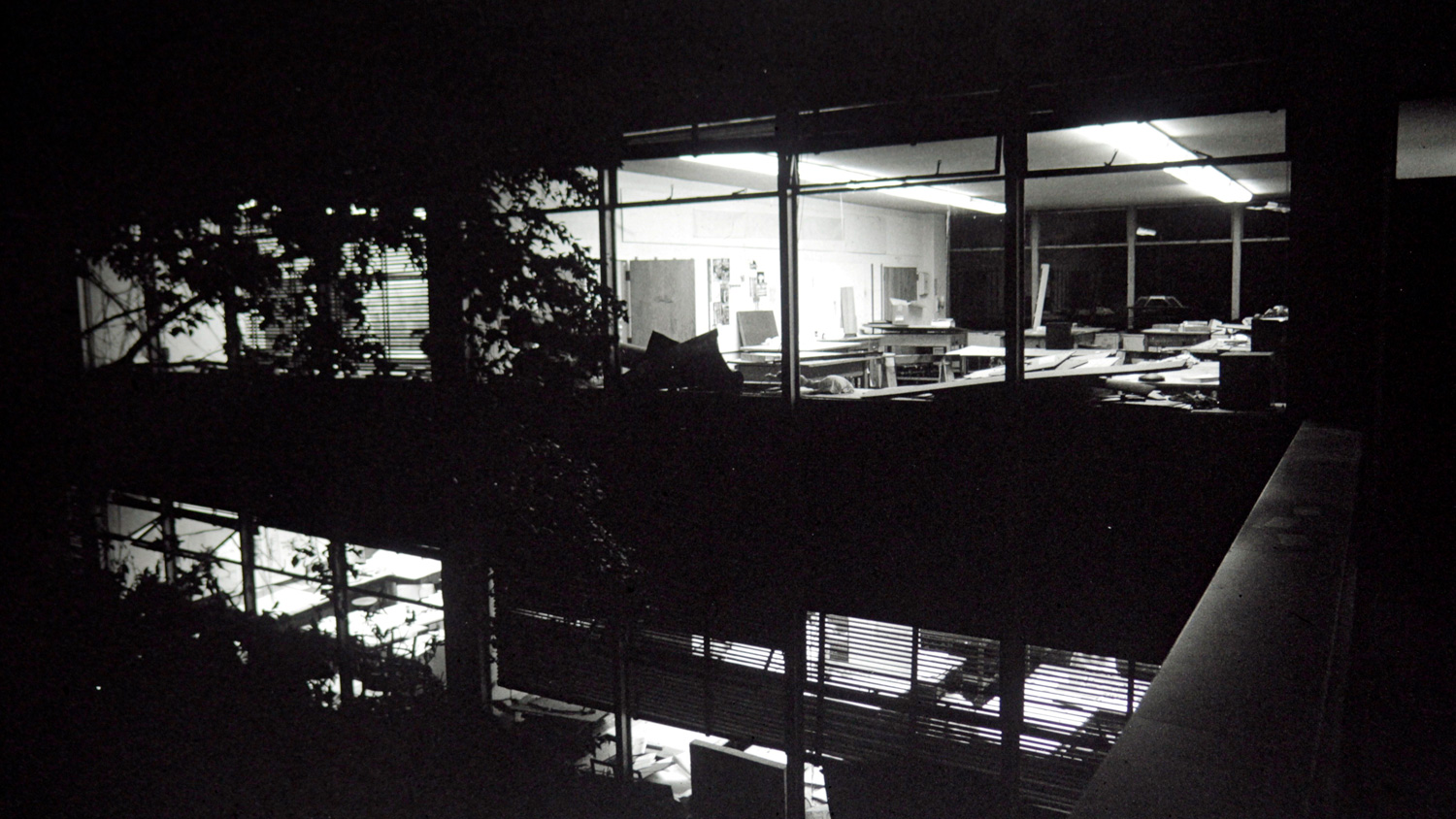

- Chancellor and university support was robust. Initially, the facilities were poor in quality. Existing offices and classrooms in what is now called 111 Lampe Drive (previously called Daniels Hall) were used, but many studios were housed in relocated military barracks near Patterson Hall. However, the university quickly made significant capital improvements for the school. in 1955 the school moved into Brooks Hall, which was D.H. Hill, Jr. Library. It was renamed for Eugene Brooks, the fifth president of the university. In 1956 the Matsumoto addition was built to the north. In 1966 the Cameron addition was built to the south.

- Focus was on one architecture degree program, yielding a professional Bachelor of Architecture degree in five years. For years the curriculum remained unchanged, though the content of instruction evolved based on ever-changing faculty interests. Faculty focused on their teaching and practice, less so on administrative and service tasks creating new curricula.

- Excellent students: All applicants were interviewed by the dean for admission. Rigorous standards were set; students needed to be exceedingly dedicated and hard-working.

- The Student Publication: Annual publications were produced by students working under a faculty advisor. Topics changed each year based on a competitive review of proposals. These publications were significant because they addressed cutting-edge issues outside of the school. They were disseminated to bookstores, architectural offices and libraries worldwide. They showed the intellectual flavor of the school, and its design acumen as seen in the printed artifact. These spread the reputation of the school more effectively than any university catalog. Many subsequent students and faculty first learned about the school through these publications.

- Art Auction: Proceeds from the sale of The Student Publication were rolled over for the next publication, but more funds were needed. An annual Art Auction was held each spring in which students and faculty would donate works of art, drawings, sculptures, and models for sale, with some proceeds supporting the next publication. Again, creative works were disseminated and publicly praised, enhancing the reputation of the school.

In 1970, three years before Henry Kamphoefner retired as dean, the architecture program began to transition to more diverse paths toward architectural education, largely due to national trends. The most notable of these was the transition from the five-year Bachelor of Architecture degree as the only degree path to a four-year non-professional architecture degree with an optional two-year professional Master of Architecture degree following. This 4+2 degree model was manifest here as a 2+2+2 sequence, in which the first two years of basic design were common to all undergraduates in the School of Design.

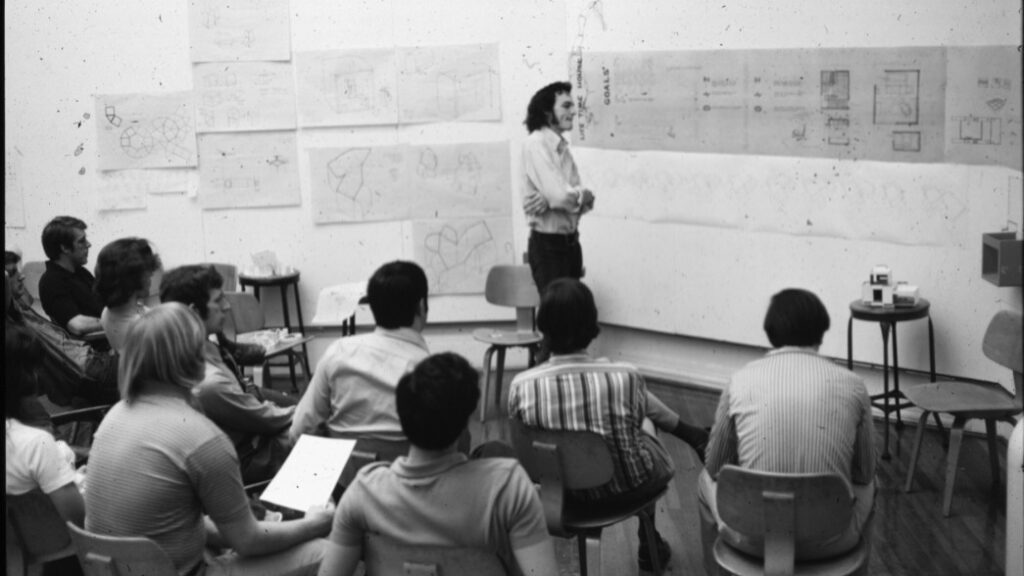

Several other changes followed, as Dean Claude McKinney (1973-1988) deferred to faculty to conceive and deliver design education, extensively empowering school-wide committees for governance. Among these changes were the following.

- Core topics were commonly taught: In addition to a two-year design fundamentals program, six “cores” were established in graphics and communications, behavior, environment, history and philosophy, physical elements and systems and methods and management. All non-studio courses in the school were organized into these cores and made available to undergraduate and graduate students for all degrees. Undergraduate architecture students were required to take at least one course in four of the six cores. Interchange between majors and degree levels was to be facilitated.

- School-wide committees overlayed departments: Courses and curricula, undergraduate admissions, faculty searches, promotion and tenure decisions, exhibitions, visiting lectures and many other areas were managed by committees composed by faculty from all academic units. One undergraduate and one graduate student served on each of these committees, with voting rights.

- New degree programs were created: Product Design had begun in 1958; Visual Design was added, initially as a program within Product Design. Design Fundamentals was also added, later to become Art and Design. Graduate studies in each department were initiated.

In the 1980s, other changes began under Dean McKinney, then continued under Deans Thomas Regan (1989-1994), and Marvin Malecha (1994-2015). They continue now under Dean Mark Hoversten (2015 – present). The most notable of these were:

- New faculty models were introduced: A transition from the initial emphasis on teaching and the education of the next generation of designers, as might be appropriate for a land-grant university, to broader and more diverse models. Graduate education, starting with masters-level degrees, but later PhD in Design and Doctor of Design degrees would be introduced. These programs attracted more university support than undergraduate education. The metrics of a Research-1 University affected these decisions. With these new models, faculty sometimes taught less and pursued research, preferably externally funded research, which had the potential to financially benefit the school and university in ways that became necessary as support from the NC Legislature diminished.

- Centers were created: As clusters of research projects arose, they sometimes led to academic or non-academic units that engaged faculty and students, sometimes supplemented by professional staff to carry out projects. The Community Design Center and the Center for Universal Design are examples that were relevant to architecture.

- Doing more with less: As enrollments in architecture increased, as degree options increased, and as new faculty models were introduced, it is important to note that the number of architecture faculty stayed the same, or even declined. The number of full-time faculty in architecture peaked at 17 in the early 1970s. We now offer a wide array of architecture degrees, and do so with only 14-16 full-time faculty members, and two faculty with dual appointments to degree programs other than architecture. Increasingly vital is the support of over a dozen professors of the practice who generously contribute their time and talent to the teaching of many studios and courses. In fact, the current curricula could not be taught if using only our full-time faculty. The architecture program has an exemplary relationship with the practice community.

People

Clarity of vision requires capable people who can articulate that vision in such a way that others can give it life. It began with Henry Kamphoefner, but he was greatly assisted by Lewis Mumford, a part-time faculty member who set out the philosophical direction and curriculum of the young school, and who urged the dean to hire Matthew Nowicki as the first department head of architecture. Though Nowicki was only able to serve as head for two years before his tragic death in an airplane crash when returning after two months working on the design of India’s new nation’s capital of Chandigarh. Nowicki’s 1950 design of Dorton Arena would be realized by his collaborator William Henley Dietrick in 1952, two years after Nowicki’s death.

Argentine-born architect Eduardo Catalano became head of architecture in 1951 and remained until 1956 when he took a faculty position at MIT. During his time as head, the stature of the architecture program grew substantially, fueled by the achievements of faculty and students.

A novel administrative model was in place between 1956 and 1967, in which Henry Kamphoefner was both dean of the school and de facto dead of the Department of Architecture.

Robert “Bob” Burns, a native of Roxboro, North Carolina, studied under Catalano here and earned his Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1957. He completed graduate studies at MIT, again studying under Catalano, and then working for several years in Catalano’s architectural practice in Boston on several substantial projects. Bob returned to Raleigh in 1965 and became one of our most important and effective faculty members. Bob was head of architecture in multiple stints beginning in 1967, adding up to seventeen years as head. During some of those years he was also associate dean for academics at the school/college level. Bob was an inspiration to the thousand or more students he taught, and to the faculty colleagues that he mentored. Many of these alums went on to leadership roles in practice and academia. In architecture faculty meetings, while many of us struggled with the complexities of the problems being discussed, Bob would step in to gracefully chart a vivid path to elegant solutions.

Clearly, the intellectual “family tree” of architecture may have begun with Henry Kamphoefner, but it continues to grow and branch into directions not foreseen by the school’s founders, through the efforts of many who came after them.

Let’s summarize here some of the means used to bring great people to the School of Design and the Department of Architecture.

- Distinguished Visitors Program: When the School of Design was founded, one faculty position was kept vacant to fund this program. During the period from 1948 – 1973, a total of 111 leading educators and practitioners came here not just for lectures, but for extended visits. This brought the most talented designers and architects from around the world to the studios in Raleigh, where students could collaborate with them on projects. This assured ongoing intellectual diversity and kept the pot boiling. This stimulating learning environment attracted educators seeking permanent faculty positions as well.

- Selective admissions: Unlike most public university departments, some of which admitted about three times more students than they intended to graduate, this program had a famously low admissions rate and a single-digit attrition rate (the percent of admitted students who do not graduate). Most of the students lost to attrition chose another major; they did not fail academically. Dean McKinney reported that School of Design majors had higher grades in university chemistry classes than the chemistry majors, and that they did better in English than the English majors. By accepting only about one-tenth of the applicants, faculty energy can be directed to teaching, and little energy is spent on students who do not matriculate. And this comes despite our focus in interviews of applicants being on the candidate’s portfolio and what they are thinking, not on their GPAs or SAT scores. In the current year’s undergraduate admissions process, again only about 10% of applicants were accepted.

Achievements

Clarity of vision, infused with talented people, often yields remarkable achievements. The architecture program earned recognition and acclaim almost immediately.

The talent and ambition of the young School of Design yielded student and faculty works that won national and international recognitions unexpected by such a new, small southern school. Faculty and visiting faculty won praise for their innovative projects carried out in practice, which were published widely. Works by Matthew Nowicki, George Matsumoto, Buckminster Fuller, James Fitzgibbons and many others are examples of this.

School of Design student recognitions took place in the most important international competitions available: the Rome Prize and the Paris Prize annual competitions. To receive eight awards within a twenty-year period was unprecedented. Winning students were the following.

Rome Prize (Prix de Rome):

- George Patton, 1949, Landscape Architecture

- Richard Bell, 1951, Landscape Architecture

- Wayne Taylor, 1959, Architecture

Paris Prize:

- Edward Shirley, 1953, Architecture

- Robert Burns, 1957, Architecture

- Edwin “Abie” Harris, 1958, Architecture

- Lloyd Walter, 1960, Architecture

- Kenneth Moffett, 1969, Architecture

Alums of the architecture program continue to earn respect at prestigious graduate programs, in excellent offices around the world, and have won countless awards and honors themselves.

Like other architecture programs in the country in the 1950’s, white males made up the vast majority of the faculty and student populations. In this context, milestones worthy of note include:

- First woman to graduate in architecture: Elizabeth E. Lee, Bachelor of Architecture, 1952

- First woman architecture faculty member: Lynn Meyer Gay, 1969

- First African American architecture graduate: Arthur J. Clement, Bachelor of Architecture, 1971

- First African American architecture faculty member: Barry Jackson, Visiting Associate Professor, 1972

For several decades the architecture program has sought university and external support to enhance minority presence, but support has been insufficient to date. Efforts will certainly continue. Regarding gender, architecture now has approximate parity in male and female student enrollment. International enrollment has recently grown significantly in the graduate Architecture programs.

ACSA Presidents:

Leadership in architectural education is another indicator of the influence of this architecture program. The following individuals were elected to serve as president of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) before, during or after being at this school.

- Henry Kamphoefner, 1963-1965, while Dean

- Robert Burns, 1979-1980, while on faculty

- Thomas Regan, 1987-1988, two years before becoming dean

- Marvin Malecha, 1989-1990, five years before becoming dean

- Linda Sanders, 1996-1997, seven years after being on the faculty

- Kim Tanzer, 2007-2008, twenty-four years after completing graduate studies

ACSA Distinguished Professors:

The ACSA Distinguished Professor Award sets out “To recognize individuals that have had a positive, stimulating, and nurturing influence upon students.” Generally, up to 5 individuals per year nationally are selected for this recognition.

(this award program began in 1984)

- Harwell Hamilton Harris, 1986

- Robert Burns, 1994

- Roger H. Clark, 1997

- Henry Sanoff, 1999

- Marvin J. Malecha, 2001

- Georgia Bizios, 2003

- Patrick Rand, 2013

- Thomas Barrie, 2018

Topaz Laureates:

The Topaz Medallion is a singular honor, one person per year nationally is chosen by a panel representing the American Institute of Architects and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Two Topaz Laureates were dean at this institution when they were selected.

- Henry Kamphoefner

- Marvin Malecha

American Institute of Architects Fellows:

Leadership in the profession is difficult to quantify. Many noble endeavors go without recognition in standard ways. The American Institute of Architects elevates to the College of Fellows individuals who have distinguished themselves in some way as architects. Each year between five and ten of these honorees are alumni or faculty from our program. Many of the part-time professors of the practice (formerly known as adjunct faculty) who teach studios and courses are AIA Fellows. This talent pool is a rich resource for our students; they serve as role models for emerging professionals. Regarding our permanent faculty, at one time, five of our fourteen full-time faculty in architecture were AIA Fellows. At that time, the only other institution in the country with five or more Fellows was Berkeley, which had 35 full-time faculty.

- Henry Kamphoefner, 1957

- Harwell Hamilton Harris, 1965

- George Matsumoto, 1973, thirteen years after being on the faculty

- Charles Sappenfield, 1974, eleven years after being on the faculty

- Richard Saul Wurman, 1976, thirteen years after being on the faculty

- Robert Burns, 1979

- Roger Clark, 1982

- Charles Kahn, 1983, twenty-two years after being on the faculty

- Peter Batchelor, 1991

- Marshall Purnell, 1991

- Marvin Malecha, 1992

- Linda Sanders, 1994, five years after being on the faculty

- Frank Harmon, 1998, two years after being a full-time member of the faculty

- Georgia Bizios, 2001

- Patrick Rand, 2007

- Gail Peter Borden, 2015, eight years after being on the faculty

- Robin Abrams, 2015

- David Hill, 2019

- Thomas Barrie, 2021

This inventory of achievements by people associated with the architecture programs certainly continues to grow. Achievements will continue in existing categories, and new categories may emerge reflecting the greater global awareness and cultural diversity of the program.

The School of Architecture continues to draw on the past and build on the foundations established by early administrators, faculty, students, and others. The school is evolving to take on the challenges and opportunities of contemporary architectural education and practice. Some examples of new programs and initiatives include the following.

- Graduate Certificate Programs: Public Interest Design, City Design, Energy + Technology in Architecture

- Graduate Concentration: History + Theory in Architecture

- Master of Advanced Architectural Studies degree program: This is a post-professional degree program. MAAS is an innovative three-semester, research-based program for students who have earned a professional degree in architecture, or a degree in a related discipline. It provides opportunities for specialized study in leading-edge areas of the built environment, and a platform to explore solutions to the crucial issues of the 21st century. Students in the MAAS program work closely with a faculty advisor who has expertise in students’ areas of study.

- Design + Build program: The School of Architecture has had a strong design-build engagement since its beginning. Each summer student teams, led by experienced faculty, design and build a project, typically for community clients. During the intensive studio, students experience and understand the design-make-design cycle, address client parameters, learn design development and construction documents phases, integrate universal design principles, respond to multiple contexts, integrate landscape and architectural design, learn collaborative design skills, and physically build a permanent project.

The School of Architecture offers many opportunities for students and faculty in multidisciplinary research, teaching, and learning: These include the following, and a growing number of others.

- First Year Experience (FYE): The Design Fundamentals program has evolved into the FYE, which continues to be a strength of our program that sets us apart from other schools of architecture.

- Duda Visiting Designer Program: The Duda Visiting Designer Program (DVDP) is a two-week immersive studio that brings prominent design professionals and organizations into the College of Design curriculum. Linda and Turan Duda, FAIA [BEDA ‘76] created the Visiting Designers Fund in 2021 to bring in national and international designers to work with the students on interdisciplinary projects.

- International experience requirement + the European Center in Prague: The School of Architecture requires each of its students to complete an international experience as part of the BEDA program. Study abroad programs in the past have taken place in the United Kingdom, Denmark, Germany, Spain and Ghana. Recently, most of our students have fulfilled this requirement by studying abroad at the NC State European Center in Prague during their senior year.

- Labs and initiatives: Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities, Coastal Dynamics Design Lab, and Building Energy Technology Laboratory (BETlab), to name a few.

- Funded/partnership studios: We partner with many external agencies and professional firms on many of our upper-level studios to provide a richer experience for our students. In recent years, we have partnered with SOM, Fentress Architects, LS3P, Hanbury, NC Coalition to End Homelessness, Durham Public Schools, Durham Parks and Recreation, NC Museum of Art, the Precast Concrete Institute, the National Concrete Masonry Association. Lenoir County (NC) and the NC towns of Nags Head, Elizabeth City, Beaufort and Princeville.

A more diverse profession is heralded by a more diverse and international School of Architecture faculty and student body. The BEDA program is ~65% women and over 30% minorities. The graduate program has achieved gender equity and draws students from the US and many other countries. We are taking on major socio-cultural and technological issues to continually address our changing world.

The celebration of the 75th Anniversary of the founding of the School / College of Design is a time to proudly reflect, but also to set new goals and boldly venture in new directions. This is the time for us to reassess the vision, engage the people and set off toward new achievements.