Designing for Resilient Communities

When Hurricane Matthew rolled up the East Coast last October, making landfall in McClellanville, South Carolina, and hugging land all the way up the Carolinas, it brought with it flash flooding, storm surge, and in some places, more than 14 inches of rain. Following a series of storms that had already inundated many of North Carolina’s tributaries, the Neuse River, Tar River, and Cashie River all overflowed their banks, devastating nearby towns and businesses. Tens of thousands of homes and structures were destroyed, and floodwaters spread toxic waste and other contaminants. The hardest-hit communities had experienced loss nearly 20 years ago when Hurricanes Fran and Floyd struck—most residents who chose to stay didn’t think such an event would happen again in their lifetimes.

The towns of Kinston and Windsor had previously been partners in collaborative projects with NC State’s landscape architecture (LAR) program. They and their neighbor, Greenville, needed help, so the LAR department postponed the regular start of classes for its spring semester to launch DesignWeek, a 10-day program focused on “Living with Floods: Eastern NC, 2050.” A steering committee that included professors in LAR (Professor and Department Head Gene Bressler, Associate Professors Andrew Fox and Kofi Boone, Assistant Professor Çelen Paşalar, and Teaching Assistant Professor Carla Delcambre), collaborator David Hill (Department Head and Professor of Architecture), and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s (UNC-CH) Gavin Smith and Mai Thi Nguyen in the Department of City and Regional Planning, sent students into neighborhoods to work with residents while considering environmental design solutions aimed at preserving community.

The Role of Design in Disaster Recovery

Traditionally, landscape architects and designers haven’t been the professionals’ people turn to when rebuilding after natural disasters. But the field and NC State’s faculty recognize that decisions about building need to be based on the land in order to reduce the possibility of future loss. The LAR faculty stand by the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s New Landscape Declaration: “The urgent challenge before us is to redesign our communities in the context of their bioregional landscapes[,] enabling them to adapt to climate change and mitigate its root causes.”

DesignWeek (or DW) was pulled together quickly to address flooding that had occurred only months earlier, but faculty considered how to prepare students for working on the ground at the scene of a catastrophe. “Andy [Fox] and his team did a really good job of setting the stage for a lot of students who probably haven’t seen or experienced disaster recovery or disasters,” said Adam Walters [LAR ’17], a graduate student and the NC State 2017 Landscape Architecture Foundation University Olmsted Scholar. “He really laid out what happened in Hurricane Matthew, how recovery happens on a very general level, and they did an exceptional job of illustrating how design can play a role in that, because that’s not obvious. It’s really interesting and somewhat novel to apply the lens of design to disaster recovery. This helps students see that there is a role for them—not an independent role, but an important part of a trifecta, in this sense of design, landscape architecture, and planning.”

The department collectively decided to delay the first week of school because “it is imperative to rally people around this,” added Fox. In addition to collaborating with the NC State School of Architecture and UNC Department of City and Regional Planning, the DW experience included interaction with various representatives from each of the focus communities, North Carolina Emergency Management, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The contributions of each group were valued, but as Fox pointed out, “Designers are built to ‘do’; others want to talk about it. The design process/design thinking is what we bring, and the student approach is what we bring. DesignWeek greased the wheels and made it apparent that designers should be at the table when discussions or decisions are being made to address wicked problems like Matthew. It was also apparent that student work matters: their outcomes were important and relevant.”

Design For and From the Community

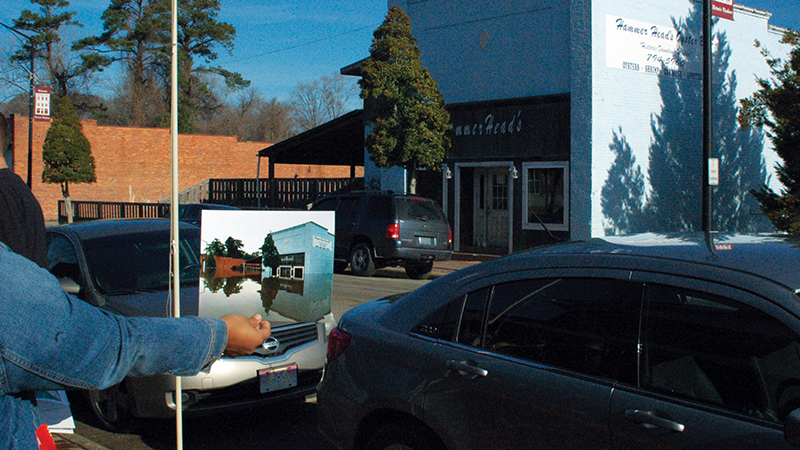

In addition to disaster recovery preparation, students needed a certain amount of exposure to the staging areas to understand what people had experienced and what they needed.

“We took groups to sites, to communities,” said Çelen Paşalar, the Assistant Dean for Research and Extension. “We wanted them to build empathy in terms of understanding what those communities actually went through and how people are feeling. They observed the destruction after the flooding, but in the meantime, they connected it to the people; they had the opportunity to meet with key groups of people and communities to understand the level of devastation that the flooding caused, what it means losing your business, losing your home. Building that empathy was at the heart of helping students understand the context, but also that the problem mattered.”

Paşalar was part of a team that went to Windsor, where 80 percent of businesses and homes had been damaged in the 500-year floodplain. Her group had to make tough decisions about what land should be bought out by FEMA and which homes could be preserved with elevation. Each community had its own challenges and needs, and the groups of students going into each were expected to plan site-specific outcomes. At the end of the week, a jury of faculty and other advisors reviewed each team’s proposal, and winning teams were selected for each site. These teams made formal presentations to the LAR department and community members.

Paşalar was part of a team that went to Windsor, where 80 percent of businesses and homes had been damaged in the 500-year floodplain. Her group had to make tough decisions about what land should be bought out by FEMA and which homes could be preserved with elevation. Each community had its own challenges and needs, and the groups of students going into each were expected to plan site-specific outcomes. At the end of the week, a jury of faculty and other advisors reviewed each team’s proposal, and winning teams were selected for each site. These teams made formal presentations to the LAR department and community members.

Walters, whose team went to Greenville, honed in on a small, low-income community of mobile homes called Belvoir that had faced exceptional losses and wasn’t receiving as much attention. “After a disaster like this, they really are even more vulnerable than they were before, not by any ill intent by anyone but because of the way a complex disaster rolls out, and a complex disaster response is always going to have people slipping through the cracks. So that really inspired us to focus on smaller communities, really vulnerable populations of folks who have been historically underserved, and how we could use design and planning to create a policy solution with design implications that could serve them.”

A number of residents in Belvoir had taken FEMA buyouts after Hurricane Floyd that were insufficient to rebuild, and many didn’t have the resources to start all over again. Most folks in this situation ultimately left the area entirely, which was the last thing community leaders wanted to see happen. “We chose to focus on small community migration away from hazard-prone areas and created a concept called the Community-Scale Assisted Migration (C-SAM) that tried to help keep the continuity and integrity of these small historic towns while moving half to two-thirds of the community out of harm’s way for future flooding events,” said Walters.

“We felt like if folks could keep the connections they have in the community and keep the integrity of the community itself, overall people would live stronger and more livable lives in this place. We developed a strategy to not just keep folks in the community but to strengthen that community’s infrastructure and livability using principles of redevelopment and greenways and landscape architecture tools to change the mental construct of ‘river as destroyer,’ which is where they started at, to ‘river as amenity,’ something that rooted their town and created an identity: river as identity.”

In Paşalar’s experience as well, there was a disconnect between residents and the nearby waterway. The county had purchased agricultural land along the sound with the goal of transforming the site into “a place for community and to reconnect the people to the water,” she said. “Although this is a community that is quite close in proximity to the water, most of the community members are afraid of water, even in the younger generation. We wanted to create that opportunity where people will be more engaged with nature and water. How can we embrace this notion of living with water? How can that site accommodate these opportunities?”

Challenges to Students and the Outcomes

Challenges to Students and the Outcomes

The compact, rapidly-unfolding nature of DW and the variety of new experiences students were faced with challenged them to adapt and learn nimbly, finding solutions much more quickly than they might in a traditional semester-long class.

“We saw that as an educational challenge for our students, introducing them to this real-time problem in the community and forcing them to be hands-on about it by understanding why this problem of flooding is reoccurring for some of these communities, and as designers, what are our responsibilities in the creation of those safe environments and the thriving future for these communities,” said Paşalar. “We try to motivate our students to think about the reality of what is happening but to be creative: what are unique innovative ideas we should be looking into but in a pressured moment, a very short amount of time?”

The 12 teams included first-year students with only a semester of LAR under their belts, as well as more experienced students like Walters. There were about 70 students in all, from the LAR program, the architecture program, and UNC-CH. They came from not just local communities but international ones, including Venezuela, Iran, and China.

Benjamin Jones [LAR ’18], although only in his first year, found himself “gravitating toward a leadership position” on his team. “I was trying to connect people and help them fit into whatever was going to be the best position for them to help us succeed,” he said. Jones learned how to use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to look at maps of Kinston and learn more about the land they were targeting.

“It kind of forced me to take on stuff that I hadn’t done,” he added. “Some of that would be the GIS, some was also looking up the policy, the local ordinances, the FEMA regulations. I took on compiling the written part of our program to then disperse throughout the presentation we were going to give, and also creating a base map, a general master plan. I also have a background in ecology, so when I started looking into the program I naturally gravitated toward an ecotourism angle: how they could redevelop their identity that tied in with the natural resources available to them, the Neuse River and state parks upstream and downstream?”

“It kind of forced me to take on stuff that I hadn’t done,” he added. “Some of that would be the GIS, some was also looking up the policy, the local ordinances, the FEMA regulations. I took on compiling the written part of our program to then disperse throughout the presentation we were going to give, and also creating a base map, a general master plan. I also have a background in ecology, so when I started looking into the program I naturally gravitated toward an ecotourism angle: how they could redevelop their identity that tied in with the natural resources available to them, the Neuse River and state parks upstream and downstream?”

Jones’ team proposed “creating a state park and an interconnected greenway system along the Neuse River and its tributaries that went through Kinston to form the basis of a new downtown.” This area would pull development away from flood-prone areas and instead focus on two of Kinston’s staples, the Neuse Sports Shop and King’s BBQ, relocating them to the north side of the river. They also suggested hosting an annual river paddling race that could bring in tourists or travelers who otherwise pass right by Kinston on Route 70.

Although Jones admitted it was tough to pull everything together in the brief time DW offered, ultimately he said, “Its value is pretty hard to argue with. The most alluring part of DesignWeek is just its connections to really relevant current issues. It’s, one, a collaborative experience across three departments, and that kind of collaborative experience is hard to come by; and I think, secondly, working with these communities that really need the help and represent extremely interesting case studies—which will be much more relevant in the future with climate change and sea rise—gives us a skillset and experience that makes us stand out.”

Anna Grace FitzGerald [LAR ’19] was stationed in Windsor, where her team discovered “once we started to take a look at the site itself, we realized it was a lot larger an issue than just flooding in the downtown area—we had to look at the whole watershed of the Cashie River.” They proposed design interventions on the headwaters such as leaky dams, an approach pioneered in the U.K. They also suggested reestablishing pocosins that were once at the bottom of the river where it drains into the Albemarle Sound, building engineered barrier islands that would act as windbreaks, “and in the town area we designed a thread of ‘seat walls’ that would double as flood walls using FEMA prototype design guidelines, tailored to work with the architecture in the area to fit seamlessly into the fabric of Windsor.” Finally, they recommended creating a stormwater management plan for the town.

“I think DW is a great opportunity for the College of Design to start to give back to the community,” she added. “Being part of a land grant organization, with the expectation to work with constituents and the community—this is a knockout way to do it. It sets NC State LAR apart from other programs. The amount of growth happening in this area makes projects like this even more important.”

“I think DW is a great opportunity for the College of Design to start to give back to the community,” she added. “Being part of a land grant organization, with the expectation to work with constituents and the community—this is a knockout way to do it. It sets NC State LAR apart from other programs. The amount of growth happening in this area makes projects like this even more important.”

Walters was struck by the diversity of the proposals. “For each different group, some people had really tangible solutions, like islands at the end of rivers, or dams that leaked; other teams had things you couldn’t put your finger on physically but that represented new ways of thinking about migration. That is what you get when you have interdisciplinary teams: you get these different outcomes and ways of thinking about solutions.

“Our students in the two-and-a-half years I’ve been here have never had a more tangible applied and intense interdisciplinary experience than that two weeks of DW, and you can tell from the products we made that they were inspired: they had depth. I’ve seen similar products come out of a 16-week studio, but we did them in basically a week. I think that was really impressive. It has had a lasting effect on the way some of our students see the role and power of design,” he concluded.

Implications for the Future

Four final DW projects received awards at the American Society of Landscape Architects Southeast Regional Conference. FitzGerald’s and Walters’ teams both received accolades. “All of the winning teams retooled their work and submitted it for the conference,” said FitzGerald.

Walters’ team’s proposal, which included C-SAM, is being considered by state agencies as a policy recommendation with the support of many resources behind it. In the meantime, he became involved with the Hurricane Matthew Disaster Recovery and Resilience Initiative, or HMDRRI. This initiative is funded through the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory and in close coordination with the governor’s office. “It’s an applied academic pursuit at the request of the governor’s office,” said Walters. “FEMA and the NC Division of Emergency Management have their practices, and those have not changed, but the governor’s office saw a need for an eye that was outside of those organizations that can help look at how the process could include resiliency.”

Additionally, discussion guides called Homeplace, tailored for individual communities, were developed over the summer. These were created to help officials and citizens understand how their towns may be affected by policies and approaches to recovery. “We want to ‘de-jargonize’ the information so that homeowners and some community leaders can understand the complexity of information and funding choices or other details that they need to know,” said Fox. Each book includes a bottom-up approach to recovery, walking communities through what to expect rather than mandating their options.

The LAR department has received a $25,000 grant from the NC State Foundation to fund DesignWeek 2018, which will include more field trips and other experiences to benefit students. Paşalar, who will lead the initiative, said, “This time we’re starting at a larger scale and we will be focusing on the Neuse River Watershed, which is the only river in North Carolina that starts and ends in the state. Along the Neuse River Basin, we have in terms of the well-known bigger cities and communities Henderson, Durham, Raleigh, Goldsboro, Kinston, and then in the end, New Bern, and between, much smaller communities being affected with what is happening along the watershed and the speed of development.”

It’s clear that North Carolina hasn’t seen the end of destructive storms and flooding, but College of Design initiatives like DesignWeek will continue to produce and support solutions for those in need.

“Something that made DesignWeek really special and unique on a national level is that we weren’t just landscape architects looking at a real, intractable issue in North Carolina—we were architects, landscape architects, and planners from NCSU and UNC, so we had these vertically-oriented teams that could extract some of the most important skills and capacities and meld them together into something that was not just creative but strong from a planning perspective and rooted in a real place with a real issue,” said Walters.

“Something that made DesignWeek really special and unique on a national level is that we weren’t just landscape architects looking at a real, intractable issue in North Carolina—we were architects, landscape architects, and planners from NCSU and UNC, so we had these vertically-oriented teams that could extract some of the most important skills and capacities and meld them together into something that was not just creative but strong from a planning perspective and rooted in a real place with a real issue,” said Walters.

“The historic role of design has an aesthetic focus, and what Andy and the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab and department at large are putting on the table is that design has a role in social justice in dealing with some of the most wicked problems of our day on the landscape and in people’s minds. I think that came out of DesignWeek, and that is still in the minds of our students.”

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of Designlife, the alumni magazine of NC State College of Design. If you would like to read additional articles from this publication, click HERE.

- Categories: