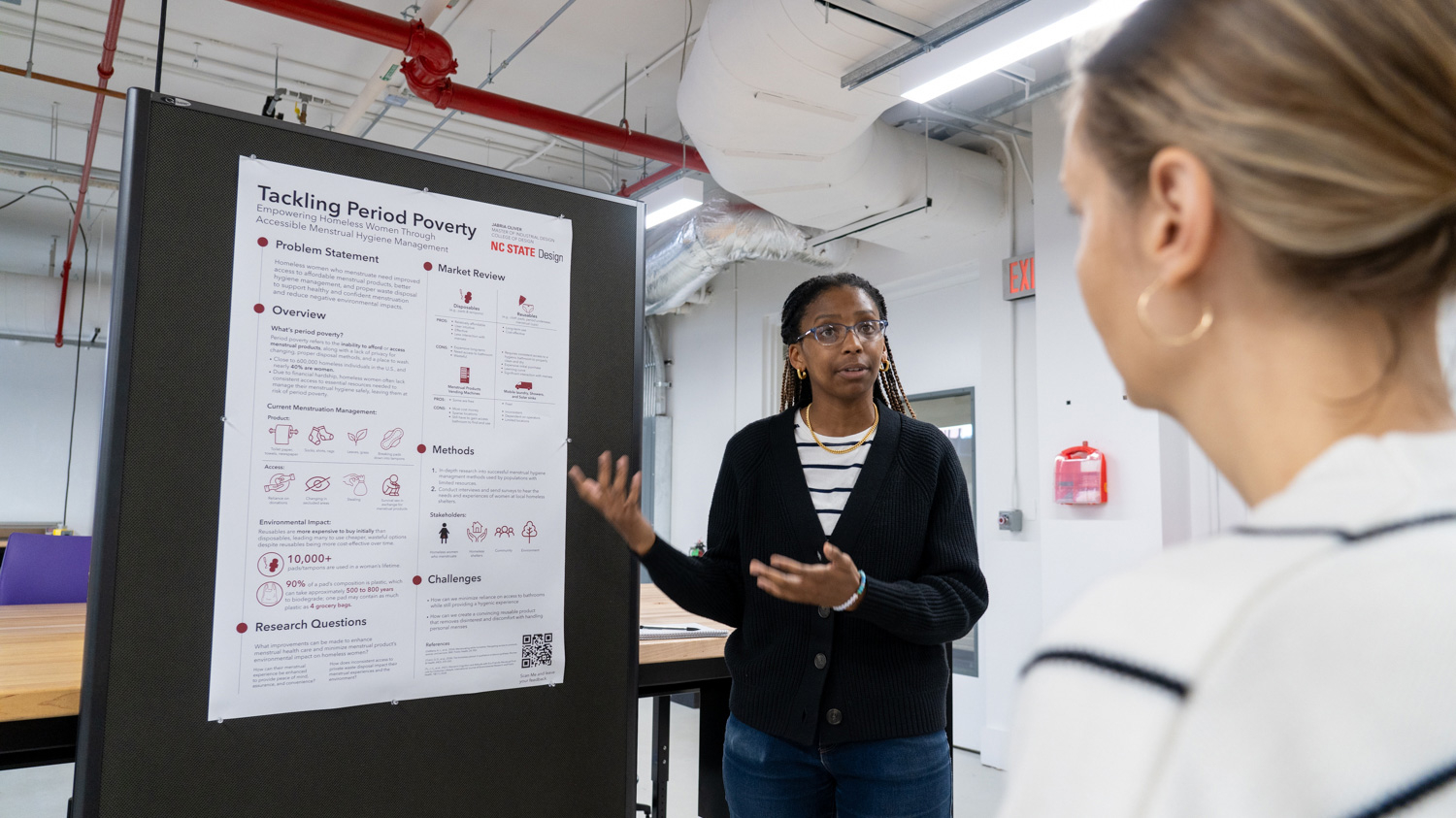

Designing Dignity: Jabria Oliver’s Fight Against Period Poverty

Period poverty, defined as the lack of access to menstrual hygiene products, safe facilities and adequate education, is a global issue affecting millions of people. For women experiencing homelessness, this often-overlooked challenge exacerbates an already precarious situation, forcing them to make impossible choices between basic needs.

In an industry crowded with consumer electronics, automobiles and medical devices, Jabria Oliver, a recent graduate of the Master of Industrial Design program, is working to create a prominent space designing for social impact.

Oliver’s connection to this issue is deeply personal. From ages five to seven, she and her mother were what she describes as “hidden homeless,” moving between relatives’ and friends’ homes before spending three months in a Chapel Hill shelter. “That experience stuck with me,” Oliver explains. “It inspired me to help others as we were helped.”

Her early experiences in other people’s homes and the shelter planted the seeds for a lifelong passion for helping vulnerable communities.

Oliver’s artistic background of drawing, painting and creating throughout her childhood eventually led her to industrial design, where she saw an opportunity to pair creativity with advocacy. “Industrial design isn’t just about aesthetics or products; it’s about solving problems and improving lives in ways that are thoughtful and inclusive,” she says.

Exploring the Complexities of Homelessness

Oliver’s research focuses on the intersection of homelessness and menstrual hygiene, an area she identifies as underexplored yet deeply impactful. “Homelessness is a massive issue with many layers,” she notes. “But the female experience is often overlooked, especially around menopause, pregnancy and menstruation.”

The complexities of period poverty go beyond the lack of products. Oliver’s work highlights the cascading challenges: limited access to restrooms and private spaces to clean or change, the stigma attached to menstruation and the unsafe conditions many women face.

“It’s not safe for a woman to be homeless,” says Oliver. “Being in a menstrual cycle makes them even more vulnerable to assault and exploitation.”

Her research revealed startling statistics, such as a study from the University of St. Louis where nearly 50% of homeless women reported having to choose between food and menstrual products.1

“That’s a ridiculous choice no one should have to face,” Oliver emphasizes. “It made me realize how critical it is to address this issue with empathy and urgency.”

Designing for Impact

Oliver’s project takes a human-centered approach involving interviews, surveys and extensive secondary research to inform her designs. She connected with

the same Chapel Hill shelter she lived in as a child to better understand the lived experiences of unhoused women. “The best design comes from collaboration,” she explains. “Listening directly to people’s stories ensures that solutions are practical and effective.”

Her potential solutions range from creating more affordable and sustainable menstrual products to imagining portable, female-friendly spaces to practice menstrual hygiene.

She also considers systemic changes, such as distributing free products through widespread networks similar to newspaper stands or addressing the high costs of menstrual products exacerbated by the tampon tax, the sales tax rate that a state, county and/or city government collects on the retail purchase of menstrual products.

Menstrual products are seen as extras because of stigma,” Oliver says. “But they’re a necessity, not a luxury.” Oliver acknowledges the broader implications of her work. “Period poverty is just one facet of homelessness,” she says. “It’s tied to systemic poverty, inequality and policies that fail to address basic human needs.” By focusing her designs on alleviating this burden, she hopes to spark broader conversations and inspire action.

Empathy at the Core

Looking ahead, Oliver envisions her work transcending homelessness to benefit women of all economic backgrounds.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many women resorted to the same makeshift solutions as those living on the streets due to supply shortages. “It’s ironic that their struggles mirrored those of unhoused women,” notes Oliver. “It demonstrates just how universal these challenges can be.”

Her ultimate goal is to create solutions that break down barriers and address systemic inequities. “I want my designs to truly listen to people’s cries, desires and needs,” Oliver explains. “It’s about creating something that solves problems and positively impacts lives, not something that ends up in a landfill.”

Oliver’s work exemplifies the transformative potential of industrial design. By combining creativity with compassion, she is not only addressing period poverty but also inspiring others to approach social challenges with empathy and understanding. “Design has the power to change lives,” she says. “It has the ability to make ‘invisible’ groups visible and create solutions that drive meaningful change for people, communities, nations, and ultimately impacts the world.”

Through her research and advocacy, Oliver offers a powerful reminder that design, at its best, is a force for dignity and equity.

This article first appeared in the spring 2025 issue of Designlife magazine. Explore other articles from this issue.

[1] Sebert Kuhlmann, Anne PhD, MPH; Peters Bergquist, Eleanor MA, MSPH; Danjoint, Djenie MPH; Wall, L. Lewis MD, DPhil. Unmet Menstrual Hygiene Needs Among Low-Income Women. Obstetrics & Gynecology 133(2):p 238-244, February 2019. | DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003060

This post was originally published in College of Design Blog.