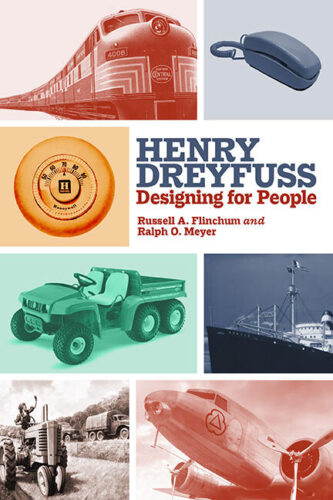

Russell Flincum, College of Design faculty, authors new book on pioneer of industrial design Henry Dreyfuss

Russell Flinchum, associate professor of industrial design, is the co-author of a new book: Henry Dreyfuss: Designing for People. The book is published with SUNY Press and is co-authored by Ralph O. Meyer, physicist and the author of Old-Time Telephones!

Henry Dreyfuss: Designing for People reveals the work of Dreyfuss’s talented, hand-picked staff and explores how together they influenced nearly a century of industrial design. With his wife as business partner, he orchestrated a firm that created some of the 20th century’s most iconic designs, including the luxury 20th Century Limited train; the interior for Eisenhower’s Air Force One; the Princess telephone; and John Deere’s Gator utility vehicle— designs that defined an entire era’s aesthetic.

This volume examines the complete history of the Dreyfuss firm. Co-author Russell A. Flinchum worked at the firm, recorded staff and family interviews, and took possession of hundreds of documents that were being discarded. Firsthand information from the firm’s two surviving partners is documented only here. The book also includes an appendix featuring five rare works that Dreyfuss had privately printed to show the scope of his firm’s work.

Flinchum provides insight on the book’s contents:

The pioneer industrial designer, Henry Dreyfuss, ran his business like an orchestra conductor, and this book is about the orchestra. Henry Dreyfuss was a New Yorker. He was born and raised in the lower reaches of Harlem; went to high school on the West Side; designed stage sets on Broadway; married the daughter of a former Manhattan Borough president from the East Side; opened an industrial design office in Midtown; and had major clients in Midtown and Downtown.

Dreyfuss’s early works include the interior and exterior of New York Central’s 20th Century Limited luxury train, which established his fame. Hundreds of Dreyfuss designs followed and are featured in five volumes of a privately printed pictorial record. Such prolific output would have required several Henrys, and indeed Dreyfuss hired help from the best talent available – from designers to sculptors to illustrators to engineers – a staff of about 30 including his wife who provided direction for the firm.

Some of the staff deserved their own stellar reputations. Roland Stickney came to Dreyfuss’s attention via a rendering of a custom-built Rolls-Royce in the window of their showroom on Fifth Avenue; his beautiful watercolor drawing of the Independence (interior by Dreyfuss) was featured in a two-page spread in the ship’s maiden-voyage brochure. Alvin Tilley, an engineer, assembled dimensional charts of average Americans called Joe, Josephine and Joe Jr. – charts that were famously made available to the public, including Dreyfuss’s competitors. Julian Everett designed toilets and vanities for the Crane Company, one of which earned Dreyfuss a Gold Medal for “Excellence in Design of Industrial Products for Architecture” by the Architectural League of New York. Donald Genaro, who often worked out practical solutions for Dreyfuss design challenges, gave shape to the Bell System’s Trimline telephone which is the only Dreyfuss work in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. And there were others.

Dreyfuss ran the firm for a full 40 years, and then the firm continued in operation for another 45 years after he retired. During that time, they designed business telephones for the Bell System, the Gator utility vehicle for John Deere & Company, the interior for the Falcon Jet Model 50, and others. Henry Dreyfuss and John Deere, the person, were long gone when work ended for Deere & Company, the Dreyfuss firm’s last client. William Crookes, then president and designer of the Gator, dissolved the Dreyfuss firm that had produced some of the best industrial designs of the 20th Century.

This post was originally published in College of Design Blog.