Through a Child’s Eyes

Assistant Professor of Graphic Design Derek Ham, PhD, is always on the lookout for ways to incorporate virtual reality, or VR, into learning experiences for kids. His own children, ages 7, 4, and 2, are “consumers of VR,” he says, but what if they could harness virtual reality as makers? “They try my higher-end Oculus Rift and VR content, so I’m always thinking of activities to get them into it. How would they make their first composition?” He wants to offer them the chance to look through a pair of VR lenses and say, “I made that!”

When Ham paired up with doctoral degree candidate Payod Panda [MID ’16] for Panda’s master’s thesis, they began experimenting with “computational thinking, spatial thinking, and spatial reasoning.” Panda was already a skilled coder, and now the duo, along with Luis Zapata [BID ’11, MGD ’17], focused their resources on constructionism in VR—the topic of Panda’s doctoral research. He paraphrases computer scientist and educator Seymour Papert: “If a learner is creating something that is shareable and viewable to other people, then the learner can have a deeper understanding of the topic.” What came next was a surprise to both Ham and Panda—and a huge opportunity for educators everywhere.

“If we talk about lowering the bar for expense and for hardware, that’s where Panoform is born, because all you need is a phone and Google Cardboard, period.” —Derek Ham, PhD

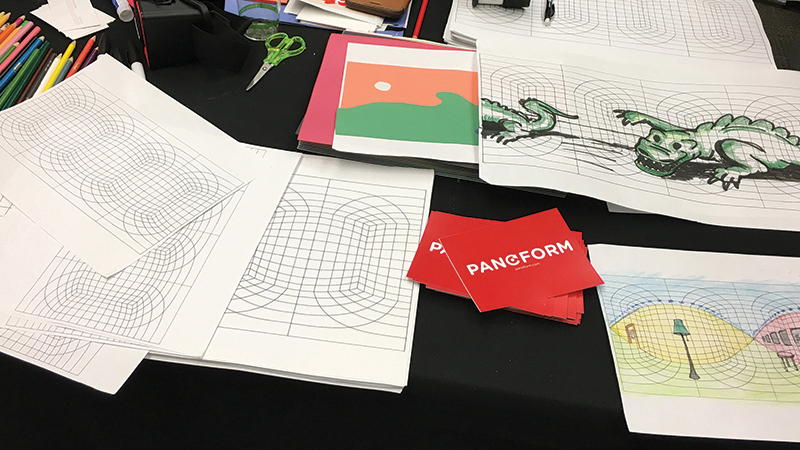

The team developed an app called Panoform, a tool that converts two-dimensional drawings made on a paper grid into three-dimensional settings. These can be viewed through an inexpensive piece of hardware called Google Cardboard, which snaps onto a smartphone. “Panoform started as an experiment, almost; we were playing around with 360 photos and VR in general, and we wanted to find a low-barrier of entry way of creating VR stuff,” says Panda.

Anyone can visit Panoform.com, print a contoured, 2-D grid, and draw a setting. After a picture on the grid is complete, it can be photographed, cropped, and uploaded to the website, where the computer reads the curve of the lines and converts the drawings into panoramic settings. The software automatically wraps and maps from the grid.

“In essence, we’re teaching kids how to deconstruct a 360-degree panoramic image,” Ham says.

As Panoform developed, it became clear that in order for it to be accessible both to younger kids and to schools, it was necessary to cut costs and take into consideration the skills younger children are learning. “If we talk about lowering the bar for expense and for hardware, that’s where Panoform is born, because all you need is a phone and Google Cardboard, period,” Ham says.

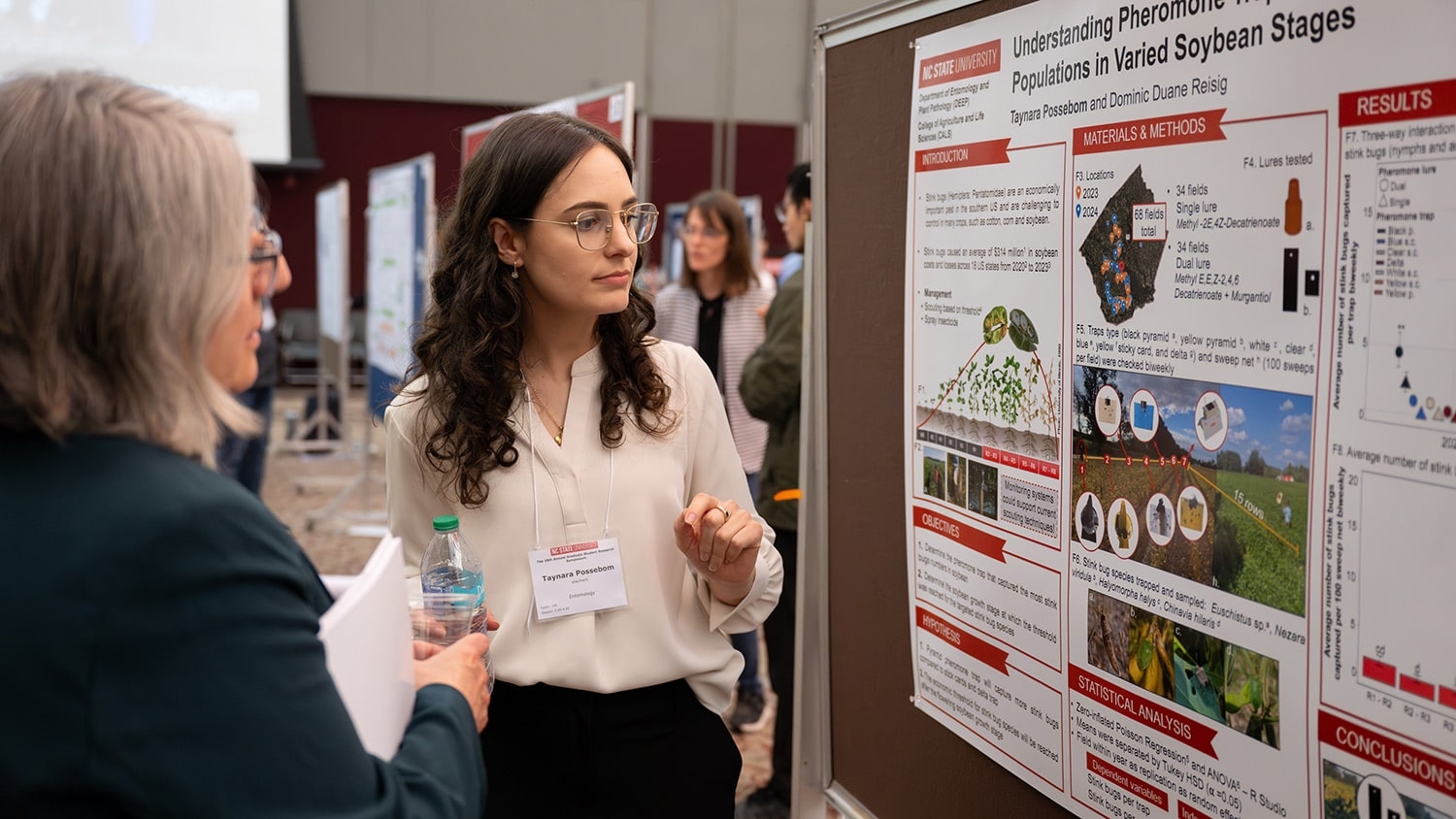

Ham and Panda presented Panoform at the SXSW EDU Conference & Festival in March, which gathers teachers and innovators over new classroom technologies. Panda presented in June at the International Society for Technology in Education 2017 Conference & Expo in San Antonio, Texas. There have been discussions of best practices and collecting data and feedback to see how Panoform impacts learning. Some teaching professionals have even reached out on Twitter about Panoform.

Lindsey Own, the Makerspace Coordinator of the Evergreen School’s BIGLab in Shoreline, WA, discovered Panoform at SXSW EDU. She introduced it to kindergarteners designing frog habitats. “I thought Panoform would be a cool way of letting the kids immerse themselves in these environments, and a neat spatial reasoning exercise for them too, because kindergarteners develop skills in being able to manipulate shapes mentally.”

To introduce the concept, Own had her kindergarteners draw a class panorama on a giant sheet of butcher paper and then wrapped the paper around groups of students so they could experience how Panoform would adapt their drawings. The project, says Own, offered students “the opportunity to look at things through different lenses and different perspectives. It was a great spatial reasoning project for the kids, and it let them create these immersive environments, which is a big learning goal that we were aiming for in the classroom.”

Own adds, “Right now, so much of VR is just consuming other people’s content, and a huge component of technology education is in kids creating their own content—Panoform is the only VR platform I’ve seen for kids creating their own VR content younger than advanced high school students, and kindergarteners can do it. It’s a really incredible platform.”

Now that its reach is expanding, Ham hopes to grow Panoform.com into more of a community site. “Right now, it’s a tool. I want to grow it so the tool is a part of a site that has everything from the blog exchange of ideas to downloadable curriculum materials, pictures—you name it. It will become a full educational website surrounding this tool and the innovative use of it, and then as we evolve the tool, it’s all part of this network of users.”

He’s also working on coloring book sheets that younger children can interact with, as well as implementing the tool in local classrooms, including the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation’s annual boot camp for teachers. Educators at Weatherstone Elementary School in Cary, NC, wrote a grant proposal on the use of VR in the classroom based on Panoform and received several thousand dollars to buy Google Cardboard devices for their students.

San Jose’s Tech Museum of Innovation will feature Panoform in Reboot Reality: a digital experience lab, a permanent exhibit with rotating platforms, including those by Adobe, Google, Facebook, and Stanford University. Described as an “experimental space,” the installation offers visitors a glimpse of many hands-on technologies, as well as workshops.

As “simple” a tool as Panoform is, “it proved really valuable to a lot of educators, which is something I was not expecting initially,” says Panda. The process of developing it has also proved invaluable to his growth as a designer, and being able to actually follow through on the creation of a design has been rewarding in a multitude of ways. “We could have had this really nice concept, but if we hadn’t been able to create it, it wouldn’t have had the response it has gotten from other educators, because nobody would have been able to use it.”

Ham imagines a future in which technology like Panoform will become ubiquitous in educational settings and beyond. As a parent and teacher, his hopes for Panoform’s reach are boundless.

“My refrigerator is covered in compositions from coloring sheets,” says Ham. “My kids made those. You go into the genre of VR, and there might be a point when a parent has a gazillion Panoform creations on their phone.”

This post was originally published in College of Design Blog.