Memorializing Flooding: How a Chance Collaboration Led to a Landmark Public Art Project

In the world of design and public art, serendipity often plays a pivotal role. This was certainly the case for a group of designers and artists who, after initially crossing paths in the College of Design, found themselves working together years later on a significant public art project in Raleigh. This project, which began as an educational initiative, ultimately evolved into a large-scale installation that engages the community on multiple levels.

Alumni William H. Dodge [M.Arch. ‘12] and Lincoln Hancock [MGD ‘10] first began their professional relationship in 2012 after working together with NC State Libraries Exhibition Designer Molly Renda. In 2019, Renda invited Dodge, who recruited Hancock and his wife Mollie Earls [BAD ‘03] to collaborate on their ongoing land art project ‘From Teosinte to Tomorrow,’ a project for the Gregg Museum of Art & Design’s exhibition “Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology.” Later, Hancock and Dodge joined forces with Dodge’s good friend and frequent collaborator, Philadelphia-based landscape architect Will Belcher, to expand the scope of projects they could tackle. They founded A Gang of Three, a multidisciplinary arts and arts planning practice in 2020.

“At the time I was leading a major architecture practice and Lincoln was doing public art installations and serving on the Raleigh public art and design board,” Dodge said. Dodge had been on the public art selection committee for the new Raleigh Civic Tower, one of the largest public art projects in the history of North Carolina. Getting the chance to be on the other side of the selection committee, and better understand that process, “it was clear that if we teamed up and pulled our collective portfolios together, we could have a great chance at winning our own large-scale projects in the future.

“I was doing work that was more ephemeral,” said Hancock. “We have different but complementary skill sets, so I was interested in how we might collaborate and work together. From there, it’s been about looking for opportunities and building upon them.

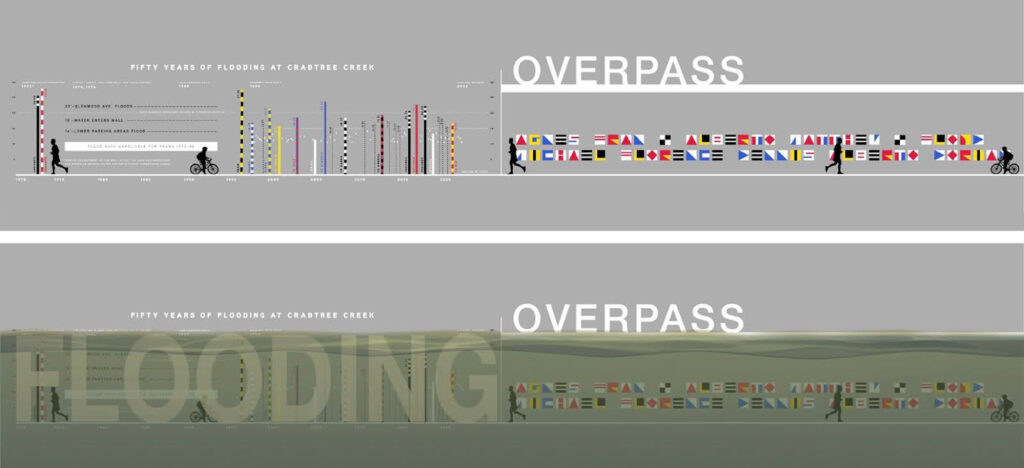

The first project they were selected for was an opportunity to create an “educational display” about the floodplain at Crabtree Creek. The resulting award-winning project, “Alluvial Decoder,” tells the story of fifty years of flooding at the site.

Alluvial Decoder: A Public Art Installation

For logistical reasons, Alluvial Decoder was originally funded as an “educational display” by the City of Raleigh’s Stormwater Management Division. However, the project quickly evolved into something much more profound. The installation is located alongside Crabtree Creek, a site notorious for flooding, and it visually represents the history and impact of these floods. Using color-coded storm markers and environmental graphics, the installation offers a visceral experience for viewers, allowing them to comprehend the scale of flooding events that have shaped the area.

“It was an interesting opportunity at a site that William and I were both really familiar with, having grown up nearby,” said Hancock. The team developed their initial ideas for the project in consultation with Raleigh Arts and Raleigh Stormwater. “As a designer and artist, I don’t see a hard line between work that’s expressive and artistic and work that’s systematic and intentional.”

Personal Connections and Community Impact

The project holds deep personal significance for the team. They recruited longtime friend Luke Buchanan [BEDA ‘02] to help create a mural that is integral to the project. Buchanan and Dodge first met in 1996 at the funeral of their mutual childhood friend, Jackson Griffin, who drowned in the flooding at Lassiter Mill in the aftermath of Hurricane Fran—a direct result of flooding at Crabtree Creek. After unsuccessfully trying to pull his friend to safety, Buchanan had to be rescued from the water himself by a bystander. Poignantly, Buchanan and Dodge completed the mural together on the 25th anniversary of their friend’s death.

This personal history—combined with Dodge’s urban planning and exhibition experience, Belcher’s landscape architecture expertise, and Hancock’s longstanding involvement in public art and installation—informed the team’s approach to the project. The team wanted the installation to resonate with the community, both as a reminder of the dangers of flooding and as a celebration of resilience, all while inviting new visitors to explore a previously underutilized portion of the greenway.

Challenges and Innovations

Designing “Alluvial Decoder” presented unique challenges, particularly the need to create a durable installation that could withstand the severe flooding that it was meant to depict. The project was also notable for its budget constraints. With only $50,000 to cover nearly two acres, the team had to be creative, leveraging their skills and networks to deliver a project that would typically require a significantly larger budget. The result is a dynamic installation consisting of a reinstituted native meadow, the aforementioned decoder mural, and 25 vertical storm markers, representing various flood events via their height—all of which transform the site into an immersive experience, educating the public while also serving as a poignant memorial.

“We were able to cover two acres and create a meaningful project that typically would cost hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars,” said Dodge. “We wanted this to be the best project it could be, and we were personally invested in its success,” added Hancock. “So every penny from the project budget went to materials and installation — we didn’t pay ourselves for our work as artists or contractors.”

‘Alluvial Decoder’ is more than just a public art project; it is a testament to the power of collaboration and the importance of community-focused design.

“By using markers that are visible from surrounding roads, we are expanding awareness of the site, and drawing in people who might not know about its history. We want to peel back the layers of what’s happening there for those who may just be using the path for recreation. And we really wanted to engage the greenway system in Raleigh. It’s such a great resource but isn’t yet widely used for art or educational moments,” said Hancock.

Both reflected on how the space they were designing could be dry one day and completely inundated with water the next. “The project is designed to flood. It can happen in an instant, with people walking their dogs or jogging, finding the path underwater in minutes if a flash flood hits,” said Dodge.

For Dodge, Hancock, and their team, this project represents the culmination of years of shared experiences, both personal and professional. It also marked the beginning of their practice as A Gang of Three and their journey towards other impactful collaborations in the future. As they continue to pursue projects and opportunities globally, they remain committed to creating meaningful, responsible and innovative designs that engage and inspire.

“We’re not right for every project,” Dodge said. “But the projects we’re right for, we’re really right for. I think there’s a huge opportunity to refocus public art on creating engaging and meaningful experiences, not just sculptural objects… and we do that as well as anyone.”

Since its completion, “Alluvial Decoder” has been honored with a number of regional, national, and international awards — including the Raleigh Medal of Arts (the only project to be awarded the medal in its 40+ year history); an Editors’ Pick – Best of Design Award from The Architect’s Newspaper; Google’s Geo for Good Impact Award; Fast Company’s Innovation By Design Award (Urban Design Honorable Mention); and honors from the American Planning Association and American Institute of Architects. It is currently shortlisted for the International Award for Public Art and a global Finalist for the 2024 World Architecture Festival (Landscape).

- Categories: