Bringing New Life to Paper Streets

Prior to a few months ago, Andrew Holland, director of performance and innovation, had never heard of the concept of paper streets. His work with the City of Durham’s Office of Performance and Innovation (OPI) meant that he and his team continually explored new ideas for improving the city. During a routine brainstorming meeting, the idea of paper streets came up in relation to code enforcement, and the team began digging into ways in which the city could tackle these often-neglected spaces.

But Holland is more than just an employee of the city. He’s also a current student in the college’s Doctor of Design program, in which mid-level professionals integrate design thinking and research practices into their professional work, connecting research to the needs of society and addressing design impacts on larger systems.

Paper streets posed the perfect project to marry these two areas of his professional work and academic research. Knowing that creative approaches to problem-solving would be a huge asset, he reached out to Carla Delcambre, associate professor of landscape architecture and environmental planning, to explore solutions with a studio full of students.

Delcambre felt strongly that the LAR 501 studio, co-taught with Professor Andy Fox, would be the perfect studio to tackle the project. “Fundamental studios, like this one, can be very abstract,” said Fox. “Students are coming into the program as mature students, bringing their own career expertise, and trying to navigate this professional shift they have chosen.”

“This project offered a very small, site-specific scale where we could introduce students to design fundamentals such as design elements and principles, and use that vocabulary to build a narrative serving as a foundation to the rest of their graduate education,” said Delcambre.

Working with the City of Durham, the students were assigned one of three sites within the city to re-envision: 1) East Peabody Street, by the Durham County Department of Public Health, 2) South Great Jones Street, by the Durham Train Station, or 3) Holland Street, situated between the Convention Center and City Hall. The sites were clustered together in the city’s downtown, allowing students to conduct field visits and imagine the scope and possibilities of their projects while standing in the space.

Student Katie Pollok was intimidated at first. She had entered the program as a Track 3 student, with no prior landscape architecture experience. But, by the end of the project, she felt confident in her design and her abilities – confirming that she had made the right choice to change professions.

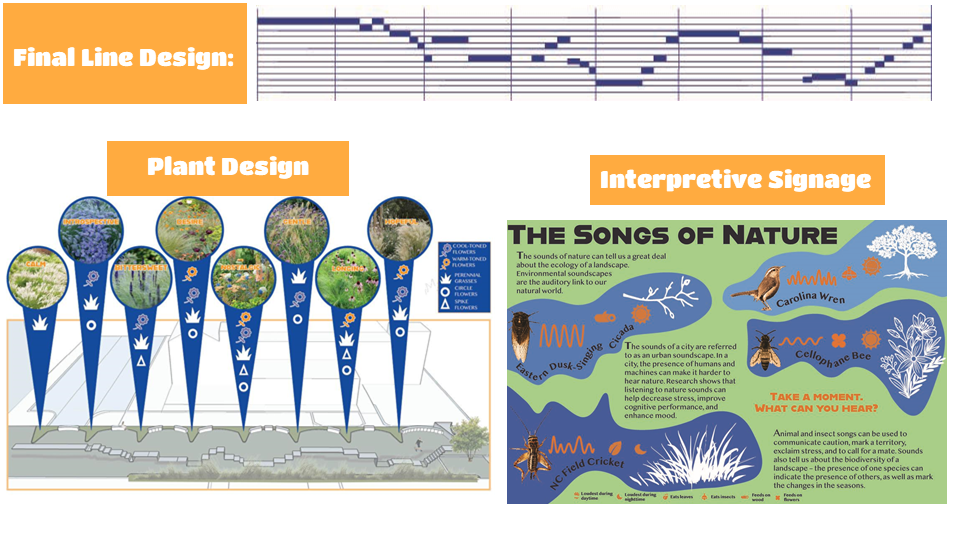

Her interpretation of the Holland Street site was inspired by the Durham Armory, where many talented musicians – Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Dinah Washington, and Duke Ellington, to name a few – performed in its heyday. Ellington wrote ‘In a Sentimental Mood’ in Durham, and her design reflects the rises and falls of the song. “I wanted to bring recognition to the flourishing music culture of present-day Durham while honoring its rich musical history,” she said.

Her design includes a winding pathway that incorporates a sense of rhythm, pattern and movement, tucked among lush shade perennials. Plantings highlight biodiversity to attract local birds and insects to make their own music in the space. Seating mimics the 8 bars of the song and lets visitors gather, rest, and engage with one another.

City officials were involved with the project from its inception, participating in mid-semester reviews and critiques. Erick Peña, innovation strategist on the OPI team, shared that paper streets are an administrative heartburn of most municipalities, creating additional burdens for the code enforcement and impact teams. Having students from an outside area look at the project with fresh eyes helped challenge ideas of what is possible for these spaces.

“The students did a phenomenal job of mixing practical implications and constraints with big-picture design ideas. It was amazing to see students take the information we shared with them and plan their designs, accounting for current and future growth in the surrounding properties,” Peña said.

“It was amazing to see students take the information we shared with them and plan their designs, accounting for current and future growth in the surrounding properties”

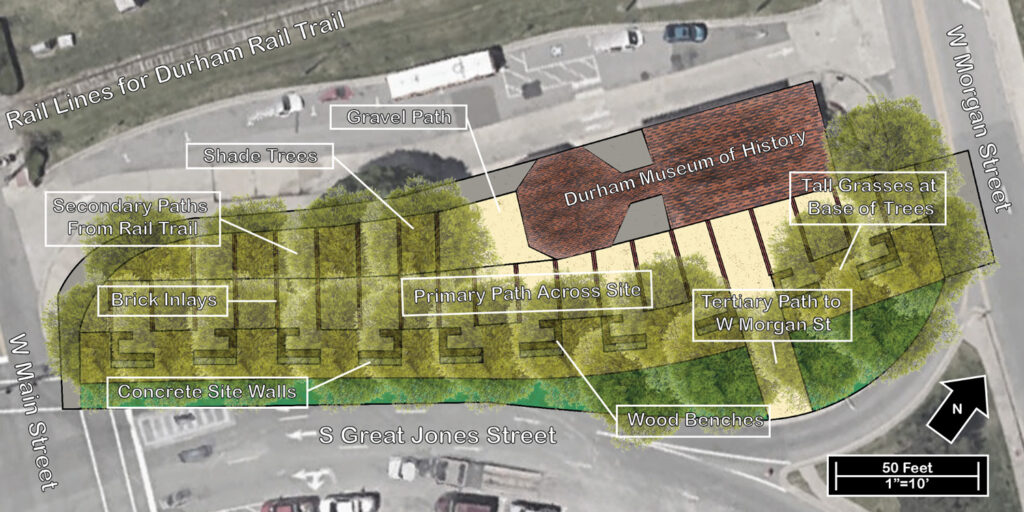

Andrew Jasperse said this was the first time he had worked on a project with actual stakeholders. His site at S. Great Jones Street tied together plans for the incoming Durham Rail Trail, incorporating inspiration from the old Southern and Norfolk rail lines that ran directly across from the museum. “Learning to tie together Durham’s history, the incoming Rail Trail project and the need for an outdoor social space for the museum made this a unique and rewarding project,” he said.

Delcambre is already planning to collaborate with the City of Durham on another studio project. This time, the focus will be on designing affordable housing for the most vulnerable individuals, particularly through tiny homes, while also considering how the surrounding landscapes can enhance a sense of dignity and community. An alumnus, Sami Allen, MLA ‘22, is a design & engagement assistant with the Office of Performance and Innovation and will partner with Delcambre on this future project.

“It’s coming full circle,” Delcambre added. “Students do this type of work in our programs, and then our graduates go on to work with the City of Durham to tackle some of these bigger, real-world issues.”

Fox felt that tackling real-world problems like this one resonated strongly with students, especially those who entered the profession intending to make an impact in the world. And since there were multiple sites to focus on, students didn’t feel a strong sense of competition to have the best project – opportunities naturally arose for peer-to-peer learning.

Halina Pyzdrowski enjoyed the iterative process of refining design concepts with peers and stakeholders alike. “Through site visits and in-studio reviews, we were able to more thoughtfully respond to unique aspects of our sites,” she said. “The result was a diverse array of ideas, distinctive to Durham – from those honoring the cultural heritage of the Hayti District, artists and industry workers to those seeking to connect residents to green space, food forests and ecological processes.”

“The result was a diverse array of ideas, distinctive to Durham – from those honoring the cultural heritage of the Hayti District, artists and industry workers to those seeking to connect residents to green space, food forests and ecological processes.”

Seeing the students tackle this project changed Holland’s perspective as a student in the Doctor of Design program, pushing his research in a new direction. “It’s really shifted my focus around simulation, and looking at how virtual reality (VR) and 3D modeling can impact a person’s perception of a particular design, specifically around paper streets.”

Durham will continue to explore mutually beneficial public-academic partnerships like this one. The OPI-Innovation Team, with letters of support from city officials and college instructors, successfully applied for and received a Love Your Block grant from the Bloomberg Center for Public Innovation at Johns Hopkins University to fund resident-led neighborhood revitalization projects.

They plan to identify one to two sites that experience a high volume of litter and will work on community engagement around those sites, holding design charettes to reimagine what these spaces could look like.

“This studio helped shift the narrative for other city staff on this issue,” said Peña. “We were impressed with the creative capacity the students brought to a local project, and how they wove Durham’s history and future into their designs.”

“It’s one thing to create a beautiful space, it’s another to create an enjoyable space that’s embedded with meaning and intention that shares a story with the public,” Pollok adds. “I appreciated doing the research, learning the history of the area, and making a design that honors that history with the goal of connecting people to place.”

This post was originally published in College of Design Blog.