Landscape Architecture Professor Lewis Clarke Passes Away at 94

Note: This remembrance is adapted from Rodney Swink’s nomination of Lewis Clarke for the 2016 ASLA Medal.

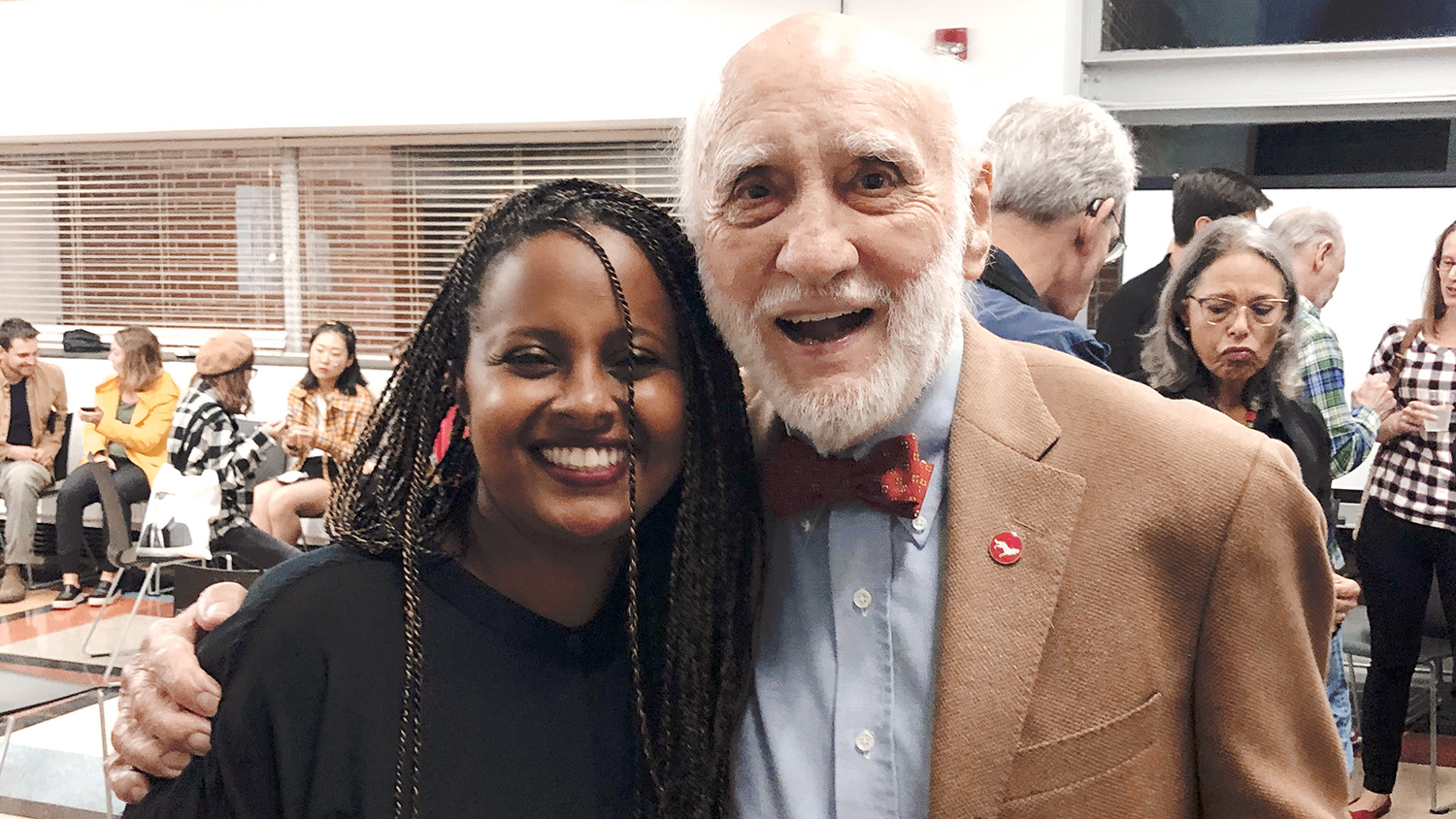

Lewis Clarke, FASLA, passed away on Sunday, June 6, 2021. He catalyzed the evolution of American landscape architecture for over sixty-five years as a professor at the North Carolina State University School (now College) of Design and as a visiting lecturer at numerous universities. Through nearly five decades of active practice, his contributions and achievements have been multi-faceted, award winning and historically significant.

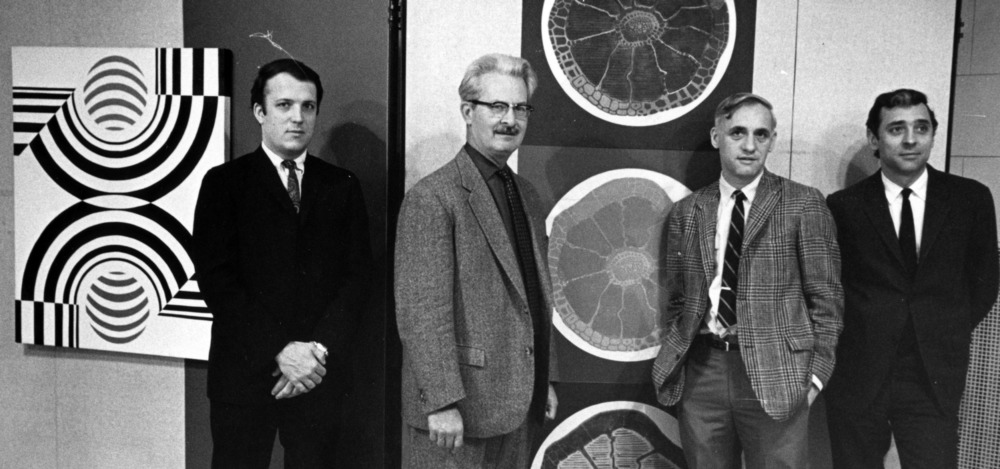

Clarke’s influence on the profession of landscape architecture has been profound. Brian Hackett, Ian McHarg and others have acknowledged his leadership in the 1950s and 60s during the discipline’s earliest efforts in adopting ecological inventory, data analysis, and overlay mapping (later advanced by Ian McHarg in Design with Nature).

Clarke was born in England. At sixteen, he began his architecture education at the University of Leicester, served two years as an officer in the British Royal Engineers, and in spring of 1950 was admitted to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). He matriculated at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1951 where he engaged Department Head Hideo Sasaki, faculty and his fellow students in testing his overlay method. Clarke’s enthusiasm coincidentally introduced architects, landscape architects, and planners to the use of ecology in environmental design.

In the fall of 1952, Clarke accepted Dean Henry Kamphoefner’s invitation to join the faculty at North Carolina State University’s four-year-old School of Design (SOD). Clarke’s broad education and international perspective had a profound influence on the development and style of the landscape architecture professional practice in the South. His work with students between 1952 and 1970 drove the eventual practitioners in groundbreaking directions where they designed at ever larger scales and in complex ecologies for newly imagined land uses. The overlay system became known as regional reconnaissance.

By 1968, demands for Clarke’s talents as a landscape architect overtook his time available to teach, and he decided to practice full time as Lewis Clarke Associates (LCA). He ran his Raleigh office like an atelier where former students and employees were nurtured, and went on to successful careers of their own. Clarke was sought by noted architects, especially the modernist style designers who saw his designs win ASLA, AIA Excellence and Merit Awards and Progressive Architecture Awards.

The number of projects Clarke shepherded to success is remarkable, but the variety of types give pause knowing that each design was guided by ecological and environmental considerations. For example, in North Carolina prior to 1960, there were no community colleges. Clarke designed the first dozen or so and set the campus design masterplan pattern imitated by others for the next twenty.

Clarke and his office completed nearly 1,300 projects. Like many 20th century offices, he generated thousands of hardcopy letters, photos, drawings, zip-a-tones, project booklets, time sheets and billing records.

Clarke retired from practice and closed his office in 2000. In 2007, his firm’s papers and drawings were transferred to North Carolina State University Library’s Special Collections Research Center (SCRC).

Known for his youthful energy, his environmental mindfulness and passion for design education, Clarke’s influence on the profession of landscape architecture is far reaching. He shaped the profession which he loved, and leaves behind a legacy of work that includes a variety of landscapes that are enjoyed by thousands each day.

Lewis Clarke’s legacy will continue to live on in those he has taught, served and loved for generations to come.

This post was originally published in College of Design Blog.