Joy and Pain

Artist Dare Coulter ’15 depicts both in a new picture book about the trauma of slavery.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2022 edition of the Alumni Magazine. By Sarah Lindenfeld Hall.

Sometimes Dare Coulter ’15 needed a break. The artist was trying to figure out how to illustrate a new picture book by an acclaimed writer of children’s fiction, but the topic was dark — the impact and trauma of slavery. Coulter’s journey took her to its horrors — harrowing stories of Africans’ cross-Atlantic journeys and despair as families were ripped apart.

It was heavy work. The images and stories triggered nightmares. But her goal was to give life to the book’s words and create imagery that makes the trauma of slavery tangible.

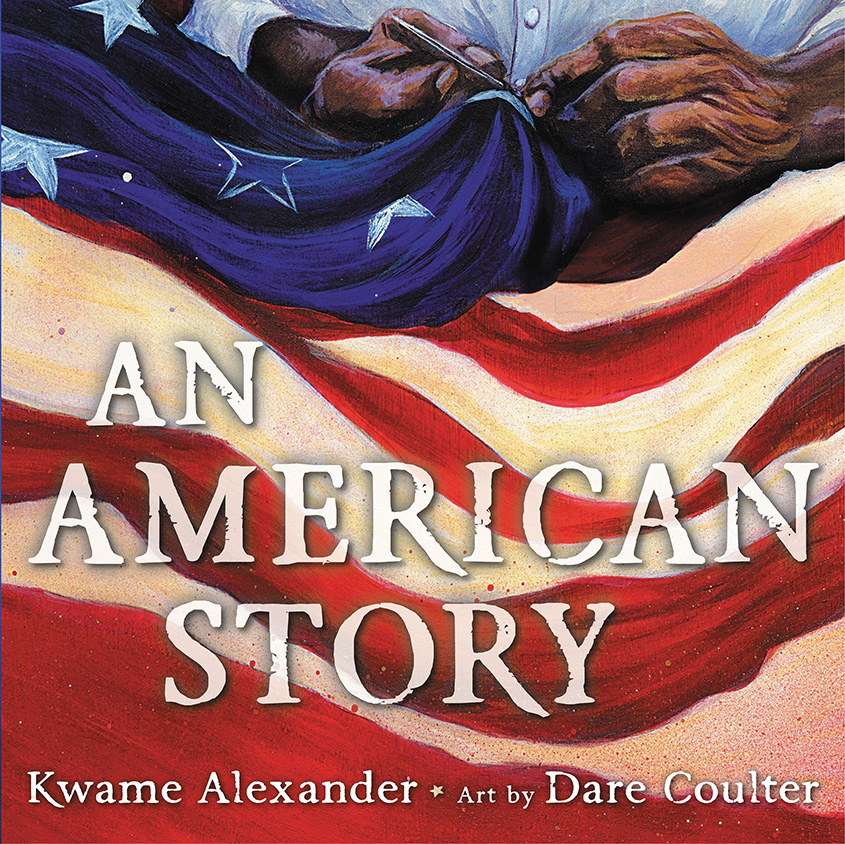

For an artist like Coulter, who has focused on portraying Black joy in massive public art pieces throughout North Carolina, An American Story might seem like an unlikely project. The story “starts in Africa and ends in horror,” as its author, Kwame Alexander, writes to begin the book. But the joy Coulter is known for belongs in An American Story too, she says: “The joy shows what’s possible, but the pain is there as a reminder.”

With an award-winning and best-selling author like Alexander attached, the book is poised to make waves in the children’s book world. And when Alexander saw the first page of Coulter’s art for An American Story, he was blown away. “She did something I was not expecting with this book. She made it hers,” he told School Library Journal. “She created art for this book that I’ve never seen in a children’s book. I think I wrote a pretty good poem that told a pretty good story, but her art, hands down, is majestic, magical. Magnificent. It’s a masterful piece of work. That’s what I think of Dare Coulter’s illustrations. Boom.”

“She did something I was not expecting with this book. She made it hers.”

– Kwame Alexander

Coulter is eager to see An American Story, released in January, in the hands of children. But she’s also aware that the book touches on topics that have lit up school board meetings in the past year amid efforts to downplay the role of slavery and racism in U.S. history. Alexander, who won the Newbery Medal — the Academy Award equivalent in children’s publishing — for The Crossover, a book in verse about middle school basketball players that is being serialized by Disney Plus, has had books on banned book lists before.

In fact, it was a “racially charged incident” in the fourth-grade classroom of Alexander’s daughter that prompted him to write An American Story. He realized many schools weren’t preparing students to “fully understand the truth about slavery,” he wrote in the book’s endnotes.

Coulter, 29, considers herself lucky to have had teachers who taught slavery in a fair and balanced way. She expects Alexander’s words and her images won’t be welcome by all, but she also believes the story needs to be told, so society can do better. “There’s this pessimism almost that says the intention is to forget about it so that people don’t know, so that it can be repeated,” she says. “And that’s scary.”

In just a few years, Coulter’s artistic career has been on an upward trajectory with commissions from the likes of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the University of North Carolina-Wilmington. Smiling, proud and powerful faces grace her sprawling murals of a quiet, peaceful Black girl along the West Ellerbee Creek Trail in Durham, protesters in downtown Raleigh and Black cowboys in Greensboro. In late summer, she was busy opening a laser cutting business called DareSay Signs and Gifts near Raleigh.

[modula id=”32925″]

Illustrating a book by Alexander is a potentially career-transforming opportunity for Coulter — and she took a unique, but risky and possibly more costly approach to the illustrations, which required buy-in from the publisher, says her agent, Rubin Pfeffer.

Instead of turning in oil or acrylic paintings, as originally envisioned, Coulter incorporated charcoal drawings, acrylic and spray paint paintings and 3D sculptures. She spent about two years creating the pieces, almost entirely from her home near Raleigh, sometimes scrapping work as she fine-tuned how best to tell the story through art. The final illustrations include photographs of her sculptures paired with her paintings or placed on sets built for each scene.

The design moves the reader between a present-day classroom, depicted in charcoal, where a teacher and students grapple with questions of slavery, and past settings in Africa and the United States, portrayed in sculpture and vivid acrylics. That visual language was intentional. The sculptures bring the historical figures — a joyful father, with whip marks, holding his babies, and a weeping mother, crying out for her son, for example — to life.

[modula id=”32931″]

Left: Two assistants work to place the sculptures in front of one of Coulter’s painting to create the final illustration. Right: A close up of Dare’s sculpture before the background painting is added. Photographs courtesy of Dare Coulter ’15.

“There’s this humaneness that happens in 3D,” Coulter says. “Part of the dismissal of the existence and pain of these people is considering them as just a thought. . . . Like a grain of rice in a bag of rice, and they don’t matter individually. But putting a person in clay, it puts them in the 3D realm. . . It makes them real.”

[modula id=”32928″]

Four pages from An American Story. Coulter used three mediums — clay, charcoal and paint for her illustrations. Book pages: Text by Kwame Alexander, art by Dare Coulter ’15.

“Putting a person in clay, it puts them in the 3D realm . . . It makes them real.”

– Dare Coulter ’15

Coulter has more in store, including two additional books, Pfeffer says. One publisher even agreed to postpone the release of another project she was working on so that her debut could be attached to Alexander because of his status. “She’s starting with a very high bar, but there’s something about Dare. It’s fitting,” Pfeffer says. “She takes big challenges and gets there.”

With An American Story’s release, her focus will shift to the kids who will pick it up. She’s hopeful it will lead to discussion and understanding. “This is not the full conversation about people being enslaved,” she says. “This is not the full conversation about abuses of people and their rights and their bodies. It’s an intro to, ‘It’s OK to feel sad about this. It’s OK to feel bad about it. It’s OK to have difficulty talking about it.

“But it’s not OK to not talk about it.’”

- Categories: