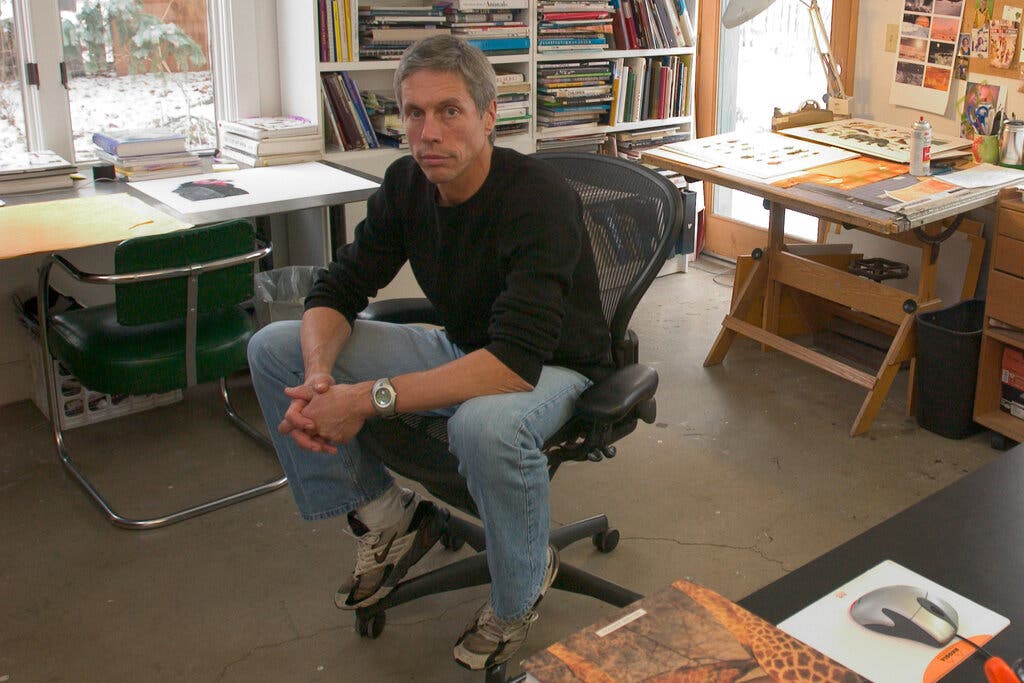

Steve Jenkins, award-winning children’s author and illustrator, dies at 69.

Stephen Wilkins Jenkins, 1952 - 2021

Republished in full from The New York Times. Written by Penelope Green.

Steve Jenkins graduated from the College of Design in 1974 with a bachelor’s degree in visual design. He then completed his master’s degree in product design in 1977. His wife, Robin Page Jenkins, holds a bachelor of visual design from 1979 from the college.

________________________________________________________________

Steve Jenkins, an award-winning children’s book author and illustrator whose passion for science, as well as his meticulous and vibrant cut-paper collages, brought the natural world to life, died on Dec. 26 in Boulder, Colo. He was 69.

His wife, Robin Page, said the cause was a splenic artery aneurysm.

How many ways can you catch a fly? And who eats flies, anyway? Why do turtles clean hippopotamuses, and how? What do you do if you work at the zoo? What do baby animals do the day they’re born? How do animals talk to each other? How do birds make a nest? His books, often written with Ms. Page, answered the sort of questions, posed by children (as well as still-curious grown-ups), about animals and the world around them.

Insatiably curious himself, Mr. Jenkins combined the rigor of scientific inquiry with exquisite illustrations and clear language to explore subjects like animal sight: His “Eye to Eye: How Animals See the World” (2014) explains how a house cat sees in the dark. (At the back of its eye is a reflective layer called a tapetum, which bounces light back through the cat’s retina.)

His “Extreme Animals” series covered the trickiest, the speediest, the deadliest and the stinkiest of animals. That last category included the European roller chick, which vomits all over itself to ward off predators. (Its vomit is so stinky because of the toxins in the grasshoppers the chicks are fed by their parents.)

His own children’s questions jump-started many books. When his daughter Page was 2 or 3, she wondered why the houses and cars she saw out of an airplane window were so small. So Mr. Jenkins made a wordless book called “Looking Down” (1995), a visual journey from outer space to a child’s backyard.

Mr. Jenkins’s medium was paper: torn (a method good for fur) or sliced with an X-Acto knife, which he assembled so precisely that his images, like the delicate shading of a rhinoceros’s baggy skin, looked as if he had painted them.

He used many kinds of paper to do so: marbleized paper; paste paper he made with Ms. Page (the paste’s rich texture makes a vulture’s black feathers pop); Japanese rice paper (for translucent creatures like jellyfish); bark paper (also good for fur); even butcher paper. He once salvaged the burned wax paper from a pizza box because he found its patterns interesting.

Over his long career, Mr. Jenkins illustrated, wrote and art-directed more than 50 books, many with Ms. Page; together they sold well over four million copies and were translated into 19 languages, including Catalan and Farsi. He also illustrated some 40 books for other authors. Among the many awards he received was a Caldecott Honor, one of the highest honors for illustration in children’s books.

“Children don’t need anyone to give them a sense of wonder; they already have that,” Mr. Jenkins wrote in 2000, when he won The Boston Globe-Horn Book Award. “But they do need a way to incorporate the various bits and pieces of knowledge they acquire into some logical picture of the world. For me, science provides the most elegant and satisfying way to construct this picture.”

Stephen Wilkins Jenkins was born on March 31, 1952, in Hickory, N.C. His father, Alvin Wilkins Jenkins Jr., was a physics and astronomy professor; his mother, Margaret Wade (Anderson) Jenkins, was a banking administrator and homemaker.

His father taught and did research at many universities, and the family moved often. Steve grew up, variously, in North Carolina, Panama, Virginia, Kansas, California and Colorado.

He was a born naturalist, collector and experimenter. “Wherever we lived,” he wrote on his website, “I maintained a small menagerie of lizards, turtles, spiders and other animals. I collected rocks and fossils. I built a chemistry lab in which many frightful smells and loud explosions were produced. With my father’s help, I assembled radios, electric motors and other contraptions. I also spent a lot of time with books.”

He thought he was headed for a career in science like his father’s. But at the last minute, he said, he pivoted to art school, earning undergraduate and master’s degrees from North Carolina State University’s School of Design. It was there that he met Ms. Page.

In 1982 he and Ms. Page opened a design studio in New York City, Jenkins & Page, which did work for American Express, Audubon, Calvin Klein, Levi’s and many other corporate clients. They married in 1984 and moved from New York to Boulder a decade later.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Jenkins is survived by their children, Jamie, Alec and Page Jenkins; his mother, and a brother, Jeffrey.

“His curiosity and passion for science and the natural world was boundless,” Margaret Raymo, Mr. Jenkins’ longtime editor, told Publishers Weekly. Over the last 25 years she and Mr. Jenkins had worked on more than 50 books together, first at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and then at Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, where Ms. Raymo is executive editor, and where Mr. Jenkins and Ms. Page’s next two books will be published.

“He always had new ideas percolating — the hard thing was to decide which one to work on next,” she said. “He wanted to get kids excited about science.”

In a phone interview Ms. Raymo added, “I always learned something when we worked together.”

Over the years, Mr. Jenkins found himself increasingly frustrated by society’s creep toward creationism and other questionable science. The idea that evolution should be considered theory and not scientific fact, or that it shouldn’t be taught at all, particularly roiled him.

A gentle, soft-spoken man whose conversational style often soothed others, he was stunned a decade or so ago when he delivered a speech to a group of educators about the dangers of ignoring scientific data or manipulating facts for political gain or financial profit, and some in the audience walked out.

“Understanding how science works means that we know how to think critically about things,” he said that day, “that we can observe things as they really appear to be, rather than as we are told they are, formulate new ideas about those things, and test them against what we already know.

“This kind of thinking,” he added, “is essential if we want to preserve some sort of control over our lives and our culture.”

__________________________________________________________

Penelope Green is an obituaries reporter for The New York Times. She has been a reporter for the Style and Home sections, editor of Styles of The Times, an early iteration of Style, and a story editor at The New York Times Magazine.