“A Diversity of Voices”: Greg Lindquist’s Environmental Painting Installations

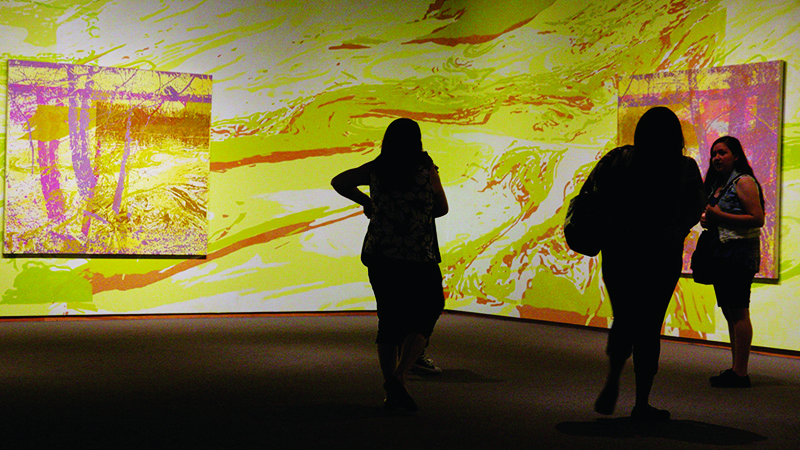

A portion of the walls in the North Carolina Museum of Art’s (NCMA) East Building are washed in layers of brilliant chartreuse and unlikely indigo paint. Dashes of murky brown are stippled with gentler pinks and lavenders. The colors feel both exotic and artificial at the same time, and the landscapes they suggest are artist Greg Lindquist’s [BAD, LAN ’03] interpretation of the coal ash pollution on the Dan River near Eden, NC, and Danville, VA.

There is beauty in Lindquist’s installation, called Smoke and Water, which immerses the viewer and draws them into the “swirling vortices of coal ash” he describes in an interview with the museum that float for about 24 hours on the river’s surface before sinking from the weight of toxic heavy metals like selenium, arsenic, lead, and mercury. And there is ambiguity—these metals are poisoning water sources by introducing cancer-causing agents, and deforming the pug-nosed fish that locals eat.

“Art can deal with contradiction in a complex way,” says Lindquist. “This is probably the most challenging thing for people. I think looking at something beautiful that’s depicting something ugly is confusing in terms of a Platonic ideal—that things look as they are, and that they represent what they do. When you crisscross those wires, it shorts people’s brains in weird ways. That’s an interesting contradiction.”

Although Lindquist doesn’t identify as an activist, he hopes to broaden awareness of the pollution caused by Duke Energy’s plant spill near Eden, NC, in February 2014, as well as a larger problem with Duke Energy plants leaking coal ash and toxic chemicals from unlined coal ash dumps. He spent four months as the NCMA’s Teen Arts Council artist-in-residence this spring, where he led discussions on environmental concerns and printed images representing the teens’ top five topics for an interactive exhibit. He also installed Smoke and Water in this period, with contributions from the teens, locals, and students of the College of Design.

Associate Professor of Art + Design Pat FitzGerald brought two of his studio drawing classes in to complete the paintings, which had to be installed in five days. “We spent an afternoon helping Greg paint from projections cast on the wall. The students really enjoyed it, and Greg shared stories of some of his efforts as a young artist in New York City. We are very proud of Greg and glad to have him back in North Carolina. His intelligence, talent, and concern for environmental causes are an inspiration to me and to the students.”

Associate Professor of Art + Design Pat FitzGerald brought two of his studio drawing classes in to complete the paintings, which had to be installed in five days. “We spent an afternoon helping Greg paint from projections cast on the wall. The students really enjoyed it, and Greg shared stories of some of his efforts as a young artist in New York City. We are very proud of Greg and glad to have him back in North Carolina. His intelligence, talent, and concern for environmental causes are an inspiration to me and to the students.”

Lindquist, who received an MFA in painting and an MA in art history from the Pratt Institute in 2008, has also used this process in a 2014 version of the project Smoke and Water in Wilmington. He made digital sketches using photos taken of the spill by local activists to inspire his paintings and projected these onto the walls, then invited residents to join in the installation process. Their statements became a part of the exhibit, testimonials to the impact of the pollution on communities in North Carolina and Virginia.

“I had to reconcile letting go of the control of wanting to do it all myself,” Lindquist says. After all, each of his original paintings require at least two months to complete. “Each touch is different, the way each participant paints is different, which I love. You can dissect the mural if you look carefully, and see all kinds of different brushstrokes, which is really a diversity of the voices of over 100 people working on it. I don’t think viewers realize this because it appears made by one singular creator.”

In a statement on his process, Lindquist writes that through these efforts, he hopes to “turn our collective anxiety into action.”

“Environmental issues are social issues,” he adds. “They disproportionately affect people of color and people of the lower classes. There is no coincidence that these electric plants are located on bodies of water because of the cooling mechanisms they need, and in areas of economic depression because poor people can’t fight corporations.”

Producing these works not only makes more people aware of the issues but gives community members a space to participate in spreading awareness. And, through his use of line and color, texture and shape, Lindquist believes his works are inviting and accessible to people without an education in art history or a knowledge of Impressionism. “I think what this installation can accomplish and what art can accomplish is engaging and exciting people and inviting curiosity and inspiration. Although I don’t know if people actually connect the impact of what will happen to the environment, I want this to bring people closer to these discoveries.”

Producing these works not only makes more people aware of the issues but gives community members a space to participate in spreading awareness. And, through his use of line and color, texture and shape, Lindquist believes his works are inviting and accessible to people without an education in art history or a knowledge of Impressionism. “I think what this installation can accomplish and what art can accomplish is engaging and exciting people and inviting curiosity and inspiration. Although I don’t know if people actually connect the impact of what will happen to the environment, I want this to bring people closer to these discoveries.”

Lindquist grew up in Wilmington, “on the beach and in the water,” he says. His father, marine biologist David Lindquist, is celebrated for installing old boxcars off the coast of North Carolina to create artificial reefs that support a greater variety of marine life. The younger Lindquist recalls spending his summers outdoors and camping with the Boy Scouts of America. For his Eagle Scout Service Project, he built a butterfly garden on top of a landfill across the highway from Duke Energy’s Sutton Steam Plant at Sutton Lake, which is now depicted in one of his paintings. “It is full circle. It fits in with the trajectory of the work; I’ve been hovering around these same ideas, but they’ve become more clearly articulated.”

More recently, Lindquist has been working with the Newtown Creek Alliance in Brooklyn, NY, to highlight similar environmental concerns on the Newtown Creek. The creek runs 3.5 miles from the East River to Bushwick and Williamsburg.

“It’s the third most polluted water in the US; since the industrial revolution on, people dumped everything in the creek from bone blacking plants that made coal tar to black wax for wagons, but also there was a huge oil spill by Exxon in the ’80s.”

Lindquist has been taking artists onto the creek in rowboats to make plein air (a phrase borrowed from French that translates to “open air”) paintings of the river. “We bring people out on the water, they make images, and those images circulate,” he says. And hopefully their impact will reach far and wide, bringing the concerns of the communities affected by this pollution to more constituents as well as lawmakers, who have the power to make greater change.

Greg Lindquist on His Work in Altered Land from The North Carolina Museum of Art on Vimeo.

Greg Lindquist is an artist, a writer, the editor of the Art Books in Review section of The Brooklyn Rail, and has taught at the Museum of Modern Art, Parsons School of Design, the Pratt Institute, Ramapo College, the Rhode Island School of Design, and the State University of New York at Purchase. The Smoke and Water installation in the North Carolina Museum of Art’s East Building is part of “Altered Land,” a show of works by Lindquist and Damian Stamer, another native North Carolinian. The pieces will remain on display until September 11.

Story by Julie Steinbacher MFA ’16

Julie Steinbacher is a transplant from Parkton, Maryland. She writes science fiction, and her story “Chimeras” was a Notable Story in this year’s Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy. She lives and works in Raleigh, NC, as a freelance writer and editor. To read her fiction, visit http://julie-steinbacher.com.

- Categories: