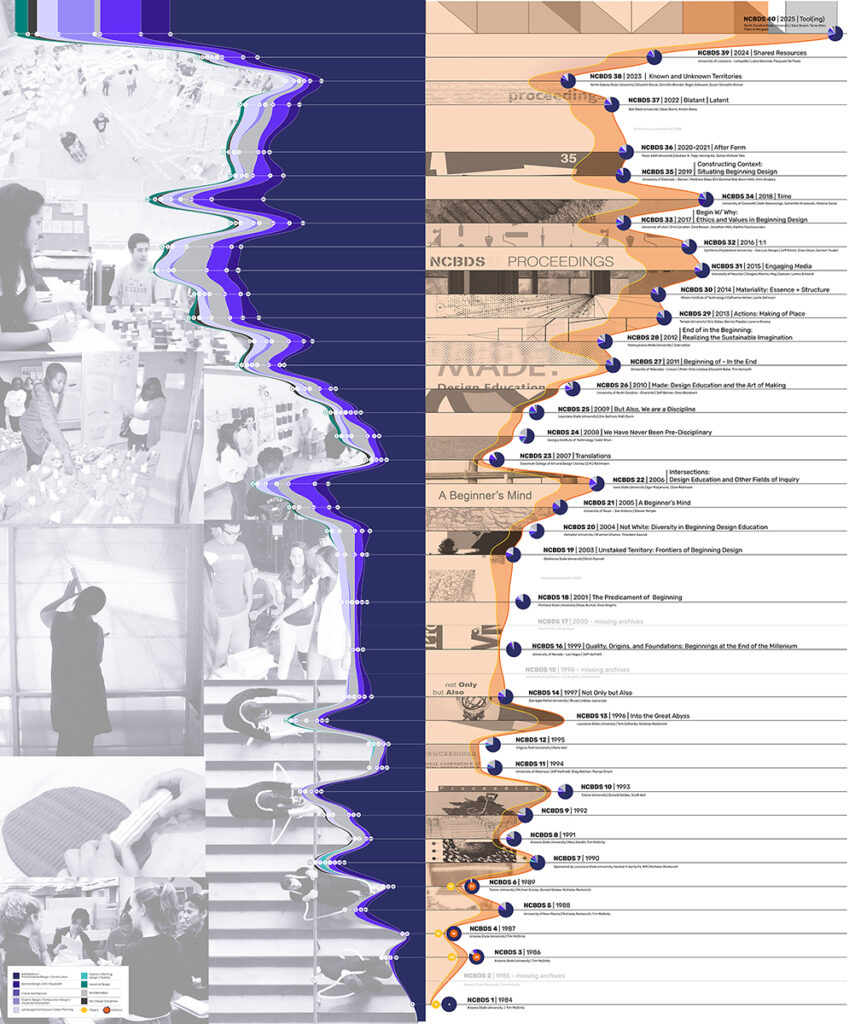

Conference Exhibit

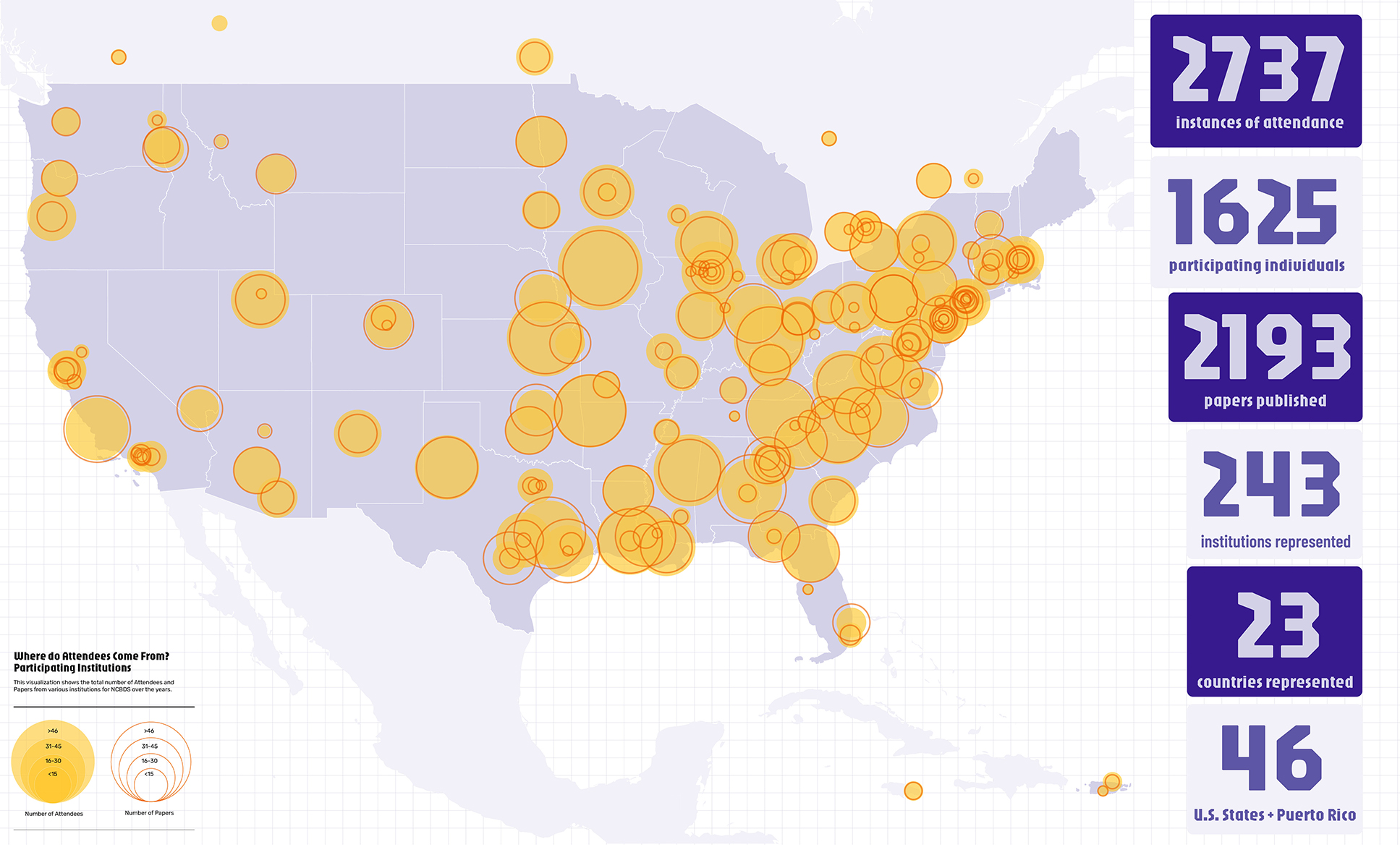

40 Years of NCBDS in Numbers

In 1970, two young assistant professors – Tim McGinty (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) and Gerry Cast (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) – were charged with teaching beginning design students. By 1972 they organized a small gathering titled “Beginnings,” a venue where early academics could share their ideas, experiences, and challenges. Eight years later, McGinty, an associate professor by then, organized a second encounter: the 1980 ACSA/AIA Teacher’s Seminar at Cranbrook Academy, titled “The Beginning Student.” This meeting attracted over 80 educators (primarily junior and recently tenured faculty) from over 60 schools, proving the need for a venue to discuss early design education. In 1984, McGinty organized what would become the first National Conference on the Beginning Design Student (NCBDS), a small seminar titled “Design Drawing” where four invited architecture professors shared their teaching methods with invited students, teaching assistants, and faculty from the southwest. No one anticipated that this meeting would be the start of a national yearly event on the topic of beginning design.

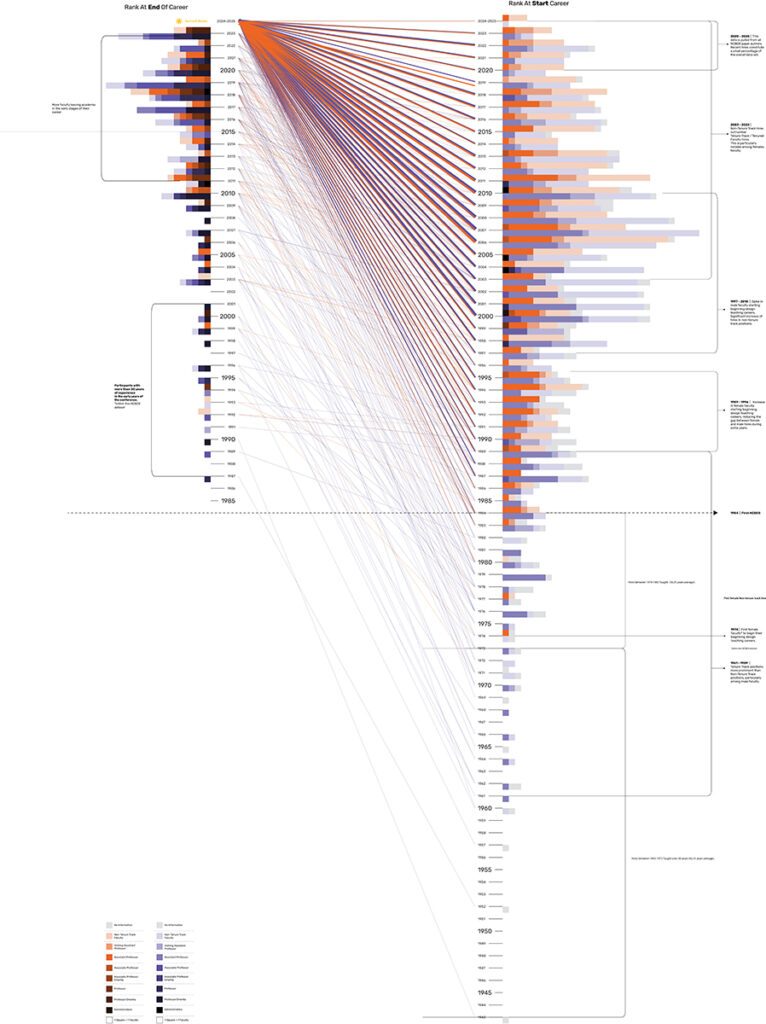

As we celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the conference, we found it pertinent to look at the conference in numbers to assess how the conference has evolved. Equally important is the analysis of how changes in academia in the last 40 years may have impacted beginning design faculty: a. the reduction of tenure/tenure-track positions in exchange for non-tenure-eligible appointments; b. the inclusion of more women, foreign born, and minorities; and, c. the change of senior faculty’s teaching responsibilities to teach advanced level courses aligned with their research area, and the hiring of temporary instructors and teaching assistants to teach the first two years of the undergraduate courses in classes with large enrollment.

An initial analysis of the academic trajectory of past conference chairs showed that beginning design education has also gone through the changes listed above. As it relates to the reduction of tenure/tenure track positions we observed that, over the years, the chairmanship of the conference has changed from primarily senior faculty (both at the associate and professors rank) during the first 10 years of the conference to mostly junior faculty and non-tenure track educators since the 29th conference. This change suggests

that experienced faculty are less involved in early education.

Regarding increase of diversity, it is important to note that over the four decades of the conference, 34.18% of the conference chairs have been women: one during the first decade, three during the second, six during the third, and 17 in the last 10 years. It is important to note is that only three conferences have been chaired solely by women.

What appears not to have changed much is diversity of race and ethnicity; to date only four chairs (5.06%), all Hispanic, are from under-represented groups. Similarly, we did not find much diversity of disciplines; only eight chairs (10.12%) were from disciplines other than architecture (three from interior design/interior architecture; two from industrial design; and three from art/studio art) and co-chaired the conference

with an architecture faculty.

Pertaining to changes in senior faculty’s teaching responsibilities, we found that over a third of the past chairs continue (and continued until their retirement) to teach beginning design, while close to two thirds moved to another area of teaching, administration, or left academia altogether. In fact, 40.84% of past chairs did not contribute papers to the conference after their chairmanship, and 11.28% have never participated with a paper. More significant is the lack of recognition that teaching beginning design receives. Only 26.92% of the faculty who continue(d) to be involved in beginning design education were promoted to the rank of professor compared to 35.55% of those who moved to other areas in academia.

In light of these findings, we considered it important to see if these were a reflection of what has taken place among beginning design educators. In doing so, we wanted to bring awareness of this to faculty and

administrators and, as much as possible, advocate for the recognition of the work of beginning design educators.

Specifically, we studied past conference

participants and their academic trajectory in order to answer the questions listed below. Data visualization was used to help better analyze and represent our findings.

- How has the conference evolved?

- Who has hosted the conference?

- How many papers were presented?

- How many people participated?

- What disciplines were represented?

- What schools were (are) represented?

- Who contributes to NCBDS, to the discourse on beginning design education?

- Where do they teach?

- How have the changes in academia in the past 40 years affected beginning design education? What changes have taken place regarding:

- tenure-track positions?

- the diversification of faculty?

- teaching responsibilities among senior

faculty? - Does Beginning Design teaching contribute to faculty advancement?

Data collection

To identify the participants of the conference in its 40 years of existence, we used the conference proceedings (and the schedules in some cases) for 37 of the 40 conferences; it is important to note that this material is missing for the 2nd, 15th, 17th, 23rd, and 24th conferences.

We researched each participants’ academic career as of fall 2024, with the goal of

identifying their discipline, rank and institution at every instance when they participated at the conference, as well as their area of expertise. When possible, we also collected information on the hiring as well as the tenure and promotion dates. For the majority of the cases, we were successful in finding the participants’ experience record, website, and contact information, but in a few cases, we were not able to find any information. This was particularly the case for the participants of the earlier conferences, as some of them have deceased.

Considering that our interest was in beginning design faculty, our data analysis does not include students (undergrad or graduate), non-teaching staff, academics from non-design disciplines, or practitioners. This first reduced our list from over 1,642 participants to nearly 1,400 educators. This list was further edited to only include those educators whose trajectory information we were able to find, which reduced our final data set to 1,151 educators hired between 1943 and 2024.

For a more detailed analysis, we invited the participants for whom we had contact information to participate in a survey on Beginning Design Educators Trajectory. We sent out 674 invitations and received 267 (39.61%) responses prior to Dec. 31, 2024. We used the information of 236 educators hired between 1970 and 2024 for whom we had a complete history of their trajectory. This data was heavily dependent on survey responsiveness and the results of our research on each respondent’s academic career, so there may be some misrepresentation of those currently teaching in beginning design.

How has the conference evolved?

From its first meeting in 1984, the conference experienced a rapid and steady growth. The number of participants in the first decade shows the need and interest for this venue, not only among architecture faculty, but also among educators from other fields. The number of participants went from four

presentations from architecture faculty in its first year to 64 papers/presentations from four disciplines at the 10th conference. In the ten years that followed, we saw a decline in the number of conference participants with an average of 37 papers per year. A second instance of growth took place between the 20th and 30th conference in 2014, when the number of papers/projects surpassed 100 for the first time. This number was relatively constant until 2020 when the conference was forced to be canceled due to Covid-19. After a short decline in participation, the number of papers / projects reached a new record at the 40th conference with more than 150. Over the 40 years, the number of participants has reached 1,642, many of them attending more than once up to a maximum of 23 times.

Also worth noting is the increase in author collaboration. During the first 10 years of the conference, the number of co-authored papers / presentations were very few, but interestingly, several of them were co-authored by junior and senior professors and in many cases at the rank of professor. From the 27th conference to today, we observed a spike in the number of authors per paper / presentation, surpassing the number of papers / presentations by 30%.

The representation of disciplines also increased rapidly. By the 3rd conference, there were three disciplines represented, and from the 7th to the 21st conference, there was an average of four disciplines. From the 22nd conference onward, with one exception, the number of disciplines represented never dropped below six. Despite the increase in the diversity of disciplines, over the years, the majority of participants by far are from architecture, followed by interior design/interior

architecture and landscape architecture.

Equally important to note is that the conference has been hosted in all five regions of the country. Specifically, it has been hosted by 34 institutions (25 public, seven private, and two Historically Black College and University) located in 22 states and Puerto Rico.

who contributes to NCBDS?

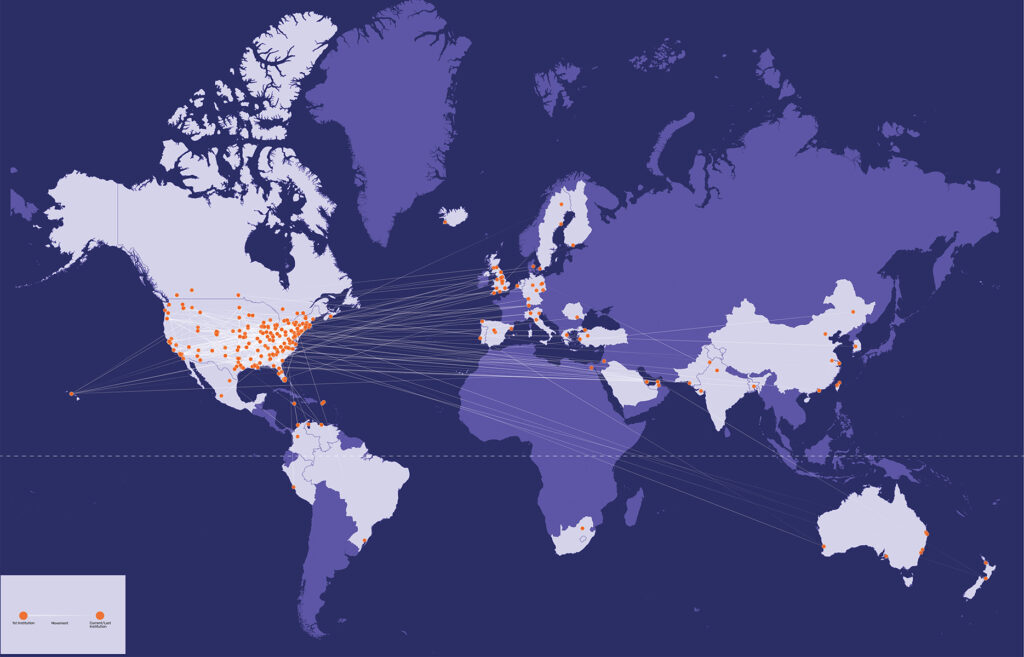

In regards to the institutions represented at the conference over 40 years, it has drawn interest from educators from 243 institutions across 46 states and 23 countries. It is worth noting that this national and international interest began in the early years of the conference. By the 3rd conference, participants came from 18 institutions (both private and public) from 13 states representing all five regions of the country. By the 7th conference, it began having participation from foreign institutions.

Historically, the conference has drawn participation primarily from US public institutions (81% of papers/presentations) followed by US private institutions (11% of papers/presentations).10 International institutions have also been present; these represent over 4% of the papers/presentations. Institutions that we found least represented were Historically Black Colleges and Universities as well as Community Colleges. In fact, papers for these type of institutions represent less than 3.5%

While the number of authors have increased, the conference continues to draw attention primarily from architecture faculty. Similarly, faculty teaching minority students are not well represented. More efforts must be made to attract participation from these groups.

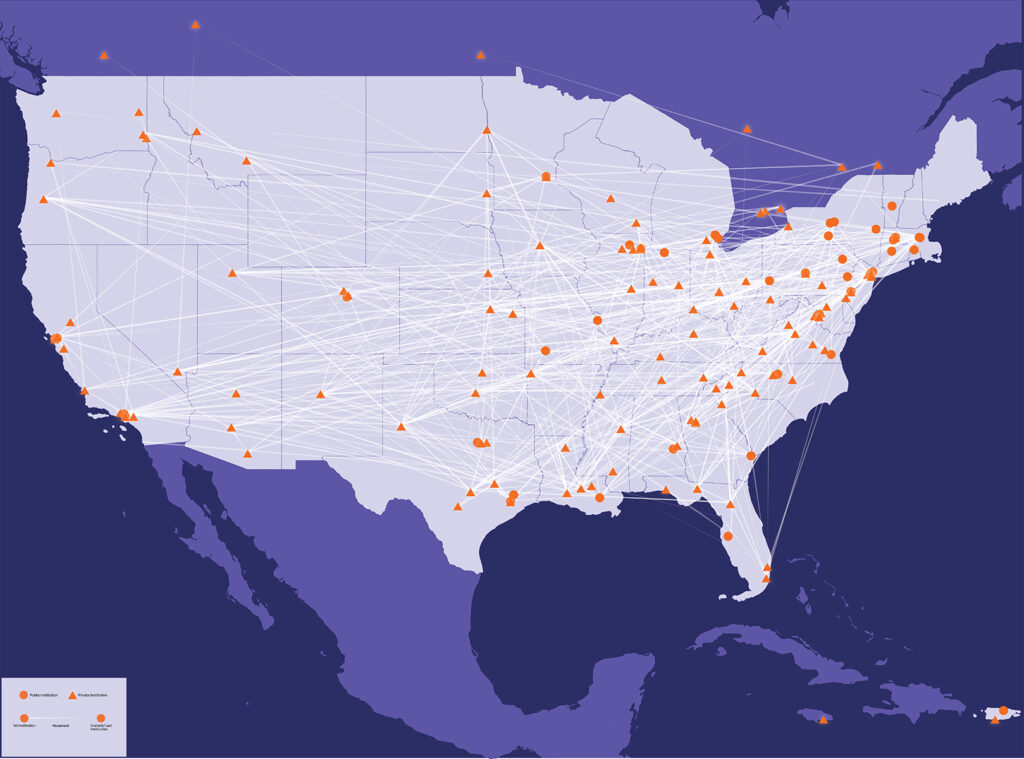

Movement between Institutions. Across the US (left) and worldwide (right)

Changes in Academia that impact Beginning Design Education

For this analysis we have used the information on 1,151 past participants to the conference, 490 (42.57%) female, and 661 (57.43%) male. (See Data Collecting for more information.)

Reduction of tenure-track positions

The study shows the progressive reduction of tenure-track positions from 1943 to 2024. As described in the introduction, this is most notable in the past 40 years. Based on the information collected, non-tenure track positions became more frequent starting in the mid 1960s. From the mid 1960s to mid 1980s, these types of positions grew to represent around 20% of the hires. Starting in the mid 1980s we observed a constant and rapid increase in these positions, going from less than 30% of the hires during the first ten years of the conference (1984-1993), to more than 60% in the last decade (2014-2024).

A closer look at the trajectory of those hired in non-tenure track positions shows the impact this has had in an educator’s academic career. Due to the reduction of tenure-track positions in the area of beginning design, it may take somewhere between three to 15 years before being hired in a tenure-track position. In parallel to this change in hiring, we saw an increase in faculty movement between institutions. This contrasts with the academic career of faculty hired in tenure-track lines who, for the most part, complete their career at a single institution, or move very little.

Hiring more diverse faculty

NOTE: Our intention was to study the diversification of faculty as it relates to gender and race/ethnicity. However, due to lack of reliable information on race/ethnicity, we focused solely on gender.

Although participants at the first conference were only men, female educators began attending the conference very early on and increased over time. Our visualization shows that the first female instructor from our dataset was hired in 1974, 31 years after the first male hiring. It would not be until the period of 1989 to 1996 that hiring of female faculty would get close in number to that of males.

Despite this increase, we observed a significant gender gap. Our research shows that women were (and continue to be) hired at lower ranks than men. Specifically, 60% of females are hired in non-tenure track and visiting assistant professor positions, compared to 54% of males. Likewise, 10% more males are hired in tenure track positions as assistant professors.

Possibly more significantly, female faculty do not advance in their academic careers at the same rate as their counterparts. A closer look at those who have left academia prior to 2024 allowed us to see that over 50% of female educators ended their career in its early stages (non-tenure track faculty positions, visiting assistant professors, and assistant professors), and only 28% reached the rank of professor/professor emerita. In contrast, over 40% of male educators ended their career at the professor/professor emeritus rank. There is less difference among faculty who leave academia at the associate professor level; this accounts to

nearly 16% for both females and males.

Among those teaching in 2024, we observed similar differences regarding academic advancement between female and male faculty. Female instructors in non-tenure track positions as well as visiting assistant professors account for over 48% while this same group among male educators reaches slightly over 34%. Also, male senior faculty surpass the number of females by 10% in the case of

associate professors and 40% in the case of professor/professor emeritus level.

While there is an increase in female faculty, there is an important gender gap that needs to be addressed.

Changes in teaching responsibilities

In addition to faculty trajectory, we were able to identify changes in the level of teaching experience of the participants in the first years of the conference. Faculty hired prior to 1984 participated in the conference up to 49 years after initiating their teaching career. This suggests that they continued to be involved in beginning design well into their academic careers. Over time, we observed less participation from senior faculty, most likely reflecting the changes in teaching responsibilities of more experienced professors and the reduction of years faculty were dedicated to this area of the curriculum.

A closer look at the date of the last paper delivered by the 1,151 faculty members being analyzed shows that faculty hired between 1984 and 1979 participated in the conference with a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 49 years of experience. Educators hired between 1980 and 1994 participated mostly in the early years of their career with as little as 2 years of experience. Among educators hired after 1994, we observed that the participation of experienced faculty with 10 or more years of experience was less and less frequent. We do not have enough information to know if this was due to faculty stopping their involvement in beginning design, or if they opted not to attend. Considering the reduction of tenure track lines and consequent increase of non-tenure track positions, we think it is likely that beginning design instruction is taught mostly by less experienced faculty.

is proudly powered by WordPress